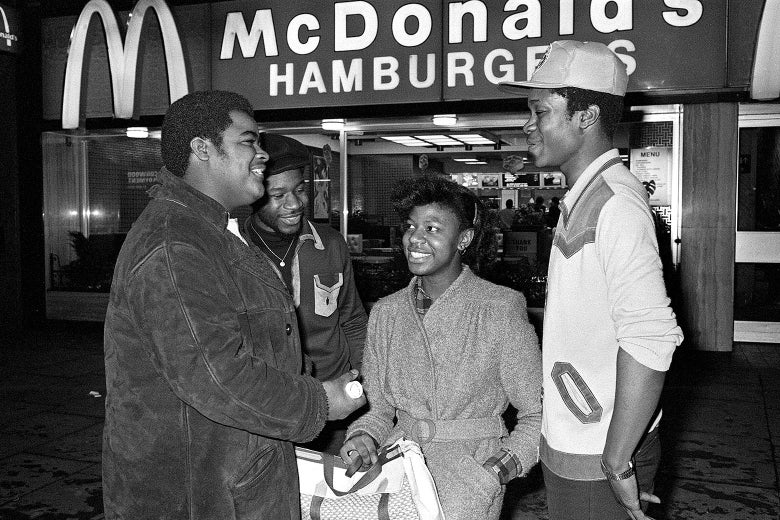

In her new book, Marcia Chatelain explores the complicated history of how McDonald’s infiltrated black neighborhoods and sold them on a boneless chicken sandwich.

When Marcia Chatelain tells people about her new book, Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America, she sometimes describes it like this: “I trace how McDonald’s became black.”

She gets a lot of bewildered responses. “People are like, ‘What do you mean? Everyone eats McDonald’s,’ ” said Chatelain, a Georgetown University history professor and my co-host on the Slate podcast The Waves. “And yes, everyone eats McDonald’s. But everyone doesn’t experience McDonald’s the same way.”

Franchise offers a deeply researched history of McDonald’s push to establish itself in black neighborhoods on its way to becoming the world’s largest restaurant chain. Black consumers and civil rights leaders faced constrained choices when McDonald’s was coming into the picture. As a target of sit-ins and boycotts, a supposed engine of black economic development, and a highly visible philanthropic actor in areas neglected by the state, McDonald’s evolved within and alongside movements for racial justice.

Christina Cauterucci: What got you interested in the racial history of fast food?

The second part of it was growing up in Chicago, just having such a familiarity with African American franchise owners as these incredibly wealthy philanthropists in all sorts of community activities. In all of the places I’ve lived, when I’ve met people of color who are from big cities, they’ve been familiar with franchise owners as real-life people. I wanted to help people think about the fact that what we eat and how we eat has a history and has a story. There’s nothing inevitable about what people are drawn to.

The familiar narrative is that fast food is popular in communities of color because it’s cheap, and there aren’t many other food options, and the food is chemically engineered to appeal to the palate. But you’re saying there’s way more to it than that.

There’s a whole political infrastructure underneath it that is supported by people that, if we take a really simple view of history, are the good guys. There is a long relationship between major civil rights organizations and the fast food industry. As a historian, when I’m teaching students, I always want people to understand that our view of history is informed by the fact that we know what happened—we know where the bad guys are lurking. But for folks who are in that particular moment, they have to use their best guesses to think about what different relationships will bear out, what kind of economic system they’ll find themselves in. In 1969 and 1970, there’s the opportunity to have a McDonald’s in your community where people can eat, they can hang out, they can have jobs, and you can see the building of something like black wealth.

From our perspective, in 2020, we can be so sure that we would never make that bad decision. But 50 years ago, people knew that businesses were fleeing the inner city. They knew that the unemployment rate for black youth was in the double digits. And they also knew that there had been a series of promises made throughout the 1960s about equality and parity that never materialized. So when you think about it that way, why not invite a corporate giant like McDonald’s into your community and see what it can do?

And some civil rights leaders were ready to make that bet. You track this shift towards black business ownership in parts of the movement after the death of Martin Luther King Jr., which seems like a surprising response, to pivot to capitalism after losing this anti-capitalist leader. How did that happen?

If you look at Martin Luther King’s last few years, he is articulating a vision for the future that is really questioning: How are people going to enjoy the expansion of housing opportunities? How are they going to enjoy better schools if they are left behind because of poverty? In his last speech, a big chunk is about economic boycott and the power of the black dollar and all of these plans that he was making with Jesse Jackson and others to think about how they could negotiate some economic gains.

I think that the reason why this pivot towards business was so strong was because that was one of the few avenues that the federal government and some white allies, both on the left and on the right, were willing to concede. The thing that I think is bananas is that if you look at the major reports that come out of uprisings starting in the 1910s up to Ferguson in 2014, these commissions will say, “Why are people so overwhelmed by the strain of racism?” And people will say, “Police brutality. Poor-quality schools. Housing that is either substandard or not affordable.” And then they’ll say, “And we don’t have enough businesses in our community.” These are really very clear problems. Yet the business one will be the one that actually has the possibility of having some movement towards it, because the business thing is easy in the grand scheme of things. Getting businesses into a community doesn’t require challenging state violence and abolishing or reforming police.

So much of this story is about black franchise owners. McDonald’s credited them with the survival of inner-city franchises during riots, and they seem to have really built loyalty in their communities. But I don’t think I know a single owner of any McDonald’s I’ve been to. Do you think that’s a big difference in the way white people and black people experience McDonald’s?

I think so. The proximity of black business owners to the everyday workings of black communities has long been a feature of the hyper-segregated world we live in. Before the franchise owners, it would be the funeral parlor owners who are extending lines of credit to people because banks won’t. Or the black banker who isn’t just taking care of a bank, but also representing the community with the sheriff or the local judge and getting involved in the historically black college.

Black franchisees are often some of the wealthiest business owners in a community. This person is everywhere. I interviewed a black franchise owner who owns dozens of outlets in Dallas, and we went to his different stores, and in his store in the black community, people know who he is because they’ve heard him on local radio. They have seen this guy donate money to their kids’ Pop Warner football. I remember watching television on the syndicated channels that would have, like, Soul Train and the black programming on Saturdays, and “the Chicagoland and Northwest Indiana chapter of the National Black McDonald’s Operators Association” was something I heard all the time growing up.

When I go to a McDonald’s, I might find the black version of whatever McDonald’s campaign or commercial cheesy or a little silly. But if I’m able to take my child in and get them a coloring book about Martin Luther King, that’s actually pretty valuable. Having spent so much time with material from the fast food industry, I have come to see it as so innovative and creative. I think about the thought that goes into the design of a tray liner that is supposed to tell you about the great African Americans in history. Or a cassette tape where Queen Latifah raps about Harriet Tubman and someone else will introduce the importance of Arturo Schomburg to collecting African American history. What I really wanted to be respectful of is the fact that sometimes when we’re critiquing the quality of goods, we are losing sight of the joy and the pleasure those goods can still produce.

There is a way that what poor people eat is portrayed as unimportant and not creative. And for me, I think it is endlessly creative and interesting—because fast food has to convince you that something that may not taste very good does.

One of the things McDonald’s did was work to convince black customers, who were suspicious of a boneless chicken sandwich, that a boneless chicken sandwich was normal and good. And, like, they were right to be suspicious! It’s a fake cut of chicken! You also write about a 1970s ad that targeted black customers, that said, basically, “Don’t worry, you don’t have to tip or dress up at McDonald’s.” Now, just a few decades later, those boneless chicken sandwiches seem normal, and that commercial seems racist. How did those norms change?

When we look back at some of the old appeals to black consumers, they are very problematic from 2020 perspectives. But by the mid 1970s, when a black consumer is going to a restaurant, they have only been federally protected to do so for about a decade. In some of my early research while thinking about a book about food and civil rights, I would talk to older African Americans about dining out, and they would say, “I remember the first time I went to a restaurant. I was in my 30s.” Or “We didn’t go places. We couldn’t go places.”

So for a number of people who are entering a place like McDonald’s in 1975, it’s still kind of a big deal. Even if it’s not fine dining and even if the food isn’t particularly amazing, the fact that you know you can walk into this place without any fear of intimidation or violence, and the manager is black and the person who owns it is black, is no small thing, nationally. For those advertisements to assure black diners that whatever traumas that you have brought or your family brought, that will not happen here, is really, really important for understanding the popularity of fast food.

And then the second part of it, in terms of what the food provides—in some instances, they had a captive market, or a market that understood the food experience as more practical than an indulgence. Fast food delivers a lot of calories, a lot of carbohydrates, a lot of sugar, really quickly. If you’re working multiple jobs, if you just need to feed yourself, it actually is a pretty good choice.

There are all of these reasons why fast food is a rational choice. What is deeply irrational to me is that we live in a system in which people can’t make many food choices because they can’t afford electricity, or their landlord hasn’t delivered a proper refrigerator for them, or they can’t pay their gas bill one month because it got really cold. But we culturally fixate on the food problems because that’s a pathway to individualize real structural inequalities that are hard to grapple with. As I’ve gone through this process, I’ve realized I’m more indifferent about fast food and probably more indignant about capitalism than anything else.

The concept of choice under capitalism animates a lot of your book. You write that, sometimes, “the choice between a McDonald’s and no McDonald’s was actually a choice between a McDonald’s and no youth job program.” How did those community choices, or lack of choices, help make McDonald’s into this dominant force in food?

It’s not a story in which no one had any agency. It’s that people had incredibly limited options and made the best out of it. What McDonald’s understood from the beginning, before it started targeting African Americans, was that it could use its brand and its economic model to ingratiate the restaurant to the larger community. So very early on, franchise owners were expected to do philanthropy and be a presence in the store. Those bonds were really important in building the brand and generating trust because people were not quite sure if they wanted a very highly trafficked business in their neighborhood. [Influential McDonald’s CEO] Ray Kroc was such a genius in that he understood what we call corporate responsibility and philanthropy as the way that you cover yourself from criticism.

When I capture some of the conflicts that people have with McDonald’s, they are often about how much McDonald’s is going to relent. If the McDonald’s is the way to get the youth job program, then how do we get a solid number of how many jobs they’ll provide? When we learn the narratives of African American history, it’s often about these really heroic choices—escaping slavery or starting an uprising. The romantic version of history is one that would say, “People were so radically anti-capitalist that they didn’t want anything to do with fast food.” But I argue that the people who sat down at the table and said, “We may not like it, but maybe this is the way we are going to extend the services of our school”— they’re probably a more realistic representation of how people actually negotiate constrained choices.

At every beat in this story, it seems like you identify a vacuum that the government left and where McDonald’s rushed in to fill the gap, to expand its own footprint. Is that how you see McDonald’s major presence in black communities? As a failure of government?

Absolutely. I see everyone failing left and right. I sometimes say that McDonald’s replaced the state in black communities. That’s such an aggressive way of describing it. But I think about it in terms of the fact that I went to pretty good schools; I got scholarships to private school.

And my first interaction with serious African American history was mediated through McDonald’s. And … good, I guess? But perhaps there could have been a place for the state to actually have provided that.

The reasons why a lot of uprisings happened in the ’60s, ’70s, and even today is because people had no space. There’s an episode of the civil rights documentary Eyes on the Prize where they talk about the Detroit uprising, and a guy basically says, “We were just outside of our houses on the stoops and in the corners. ’Cause we didn’t have parks, we didn’t have community centers. This is where we were. And these were the places where people would be terrorized by the police.” If your space is a fast food restaurant, I could tell you to stop eating cheeseburgers and you’ll say, “Thank you for your feedback.” So what I have come to think about fast food and McDonald’s is more and more not about the food they serve, but the role that they play, and how that role allows them to continue to serve the quality of food that they serve.

Between that public service role and the fact that black franchises were so profitable, which helped McDonald’s grow—it makes me think of that saying, “Black history is American history, and American history is black history.” To what extent is McDonald’s history black history, and black history McDonald’s history?

Without the African American consumer base, McDonald’s would have experienced a slowdown in the ’70s that contributed to the demise or the suppression of some of its competitors. What the African American market taught McDonald’s was that it needed to be flexible in ways that it never had to be with its suburban and mostly white markets. And once they realized that a little bit of flexibility could take them a long way, they developed the toolkit and the script that a lot of corporations use around culture and segmenting markets and understanding the appeal of crossover celebrities. All of those things were being done to some extent, but McDonald’s perfected it.

The African American contribution to shaping this industry had been erased, because there was a presupposition that black people had always been attracted to the food. When I started writing this book, people would ask me, “Did McDonald’s open their archives to you?” And no, they have a closed archive. But if we appreciate how much African Americans interfaced with this company and with these ideas of black capitalism and community building, then McDonald’s history is everywhere in the archives of African American history. And I think that that is something that I’m proudest of. This is an opportunity to push back against this idea that a group of people don’t have a history with something just because that history isn’t in the places we anticipated.

By Marcia Chatelain. Liveright.

Be the first to comment