March 7 marks the 56th anniversary of an ill-fated march from Selma to Montgomery organized by Civil Rights activists to protest unfair voting rights in Alabama. This year’s commemoration will be the first without Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.), who died last summer.

Later known as “Bloody Sunday,” the violent clash between law enforcement and protesters at the crest of the Edmund Pettus Bridge led to the hospitalization of more than 50 people, including Lewis, who was then 25 years old.

Televised accounts of “Bloody Sunday” outraged Americans of all backgrounds, and forced a sympathetic but reluctant President Lyndon B. Johnson to push for voting rights legislation.

The Long Road to Voting Equality

“The voting rights campaign was a very long campaign, and Selma was one of the culminating activities that came before the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act,” said Howard Robinson, Ph.D., assistant professor of history at Alabama State University.

“You had the ’57 Civil Rights Act, the ’60 Civil Rights Act and the ’64 Civil Rights Act, all of which had elements that spoke to voting,” he told Zenger News. “Each of the acts was supposed to alleviate some of the disenfranchisement tactics that were employed widely throughout the South.”

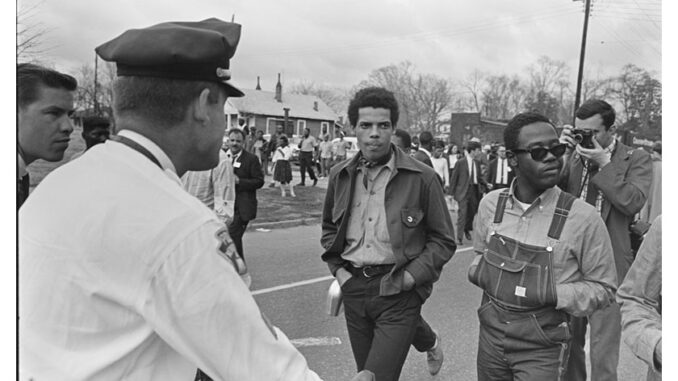

In the two years leading up to “Bloody Sunday,” the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee engaged in numerous demonstrations that led to more than 2,000 arrests.

At the same time, the Dallas County Voters League, which included local activists Rev. Frederick D. Reese and Amanda Boynton Robinson, appealed to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. to join their cause.

President Johnson exploited national sympathy in the wake of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination and increasing protests to push through the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

“Johnson expends a lot of political capital doing that,” said Robinson. “Although he is sympathetic to a future civil rights bill, that’s not at the top of his list of priorities. He wants to turn his attention to his Great Society initiatives.” Those initiatives included increased spending on health care, education, transportation and programs to address poverty.

As a stall tactic, Robinson added, Johnson enlisted King to create “the public pressure that would give him the opportunity to push for legislation in the future.”

This pressure began to build with the Feb. 18, 1965, shooting of Jimmie Lee Jackson during a nighttime demonstration in Marion, Ala.

Jackson died from his wounds a week later.

“The idea was to march Jackson’s body up Highway 80 and place it at the steps of the capital in Montgomery to draw attention to the brutality that black people were facing in Alabama,” Robinson said. “It morphed into a voting rights march, and the memorial aspects of the march were sort of lost.”

Fearing potential violence and skeptical of its effectiveness, the student organizers opted not to participate in the march. But despite his organization’s misgivings, John Lewis led the march along with Southern Christian Leadership Conference lieutenant Hosea Williams.

“[Gov. George Wallace] gives the order to stop the marchers by ‘whatever means necessary’” Robinson said. “The state troopers and irregular posse men beat the marchers, tear-gassed them and turned them around in what we now know as ‘Bloody Sunday.’”

The Ministers’ March

In the aftermath, King, who was not present at the March 7 event, implored all “people of conscience” to descend on Selma and restart the march. Incensed that one of their own, Lewis, was injured in the melee, the student committee’s leaders were eager to rejoin the march.

Meanwhile, Southern Christian Leadership Conference lawyers were in court to prevent Gov. Wallace from taking punitive actions to halt subsequent demonstrations. Instead, U.S. District Court Judge Frank Johnson, Jr. issued a restraining order barring any further protests.

On March 9, King led more than 2,000 people to the bridge but, fearing that he might violate the restraining order barring demonstrations, he gathered them in prayer and turned back to Selma.

The “Ministers’ March,” also called “Turnaround Tuesday,” outraged the student protesters.

“[The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] was livid; they smelled a sell-out,” Robinson said.

What the students did not know was that King was in secret negotiations with the White House on a voting rights bill, and that he turned the protesters around to avoid any negative impact on those negotiations.

About a week after the events of “Bloody Sunday,” Johnson made a call for equal voting rights for black Americans.

“Their cause must be our cause too,” Johnson said in his March 15, 1965, speech to a joint session of Congress. “Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.”

The speech was interrupted with applause 40 times.

Ironic Moments Help Shape the Movement and the Country

“I admire the Selma-to-Montgomery marchers,” said Dana Chandler, the university archivist at Tuskegee University. “It was a coming together of people in the defense of rights for other people. They followed a pattern of peaceful demonstration, yet they were resilient in the face of enduring abuse to push for those accomplishments.”

Visiting one such marcher, Amanda Boynton Robinson, on many occasions years later, Chandler heard stories that he said illustrated a great deal about her and others in the movement.

“She said to me one time that ‘the man that beat me [on “Bloody Sunday] died, and I’m going to his funeral,’” Chandler told Zenger. “I asked her why, and she said, ‘I need closure.’ As the funeral came to an end, the man’s family approached her, hugging her and thanking her. That says so much about the woman. All of her accomplishments were fulfilled through the laws of Christ, and that’s how many others in the movement felt.”

In a larger context, the events of “Bloody Sunday” laid bare a cruel irony. On that night Americans were glued to ABC Television’s presentation of the 1961 movie “Judgment at Nuremberg,” which depicted the horrors of Nazi bigotry during World War II, until ABC News anchor Frank Reynolds interrupted the broadcast to report the violence in Selma.

“As part of the [Cold War] propaganda, the United States was taking a beating over civil rights because it was arguing … that Third World countries should implement a democracy and let the public participate in the electoral process,” said Robinson. “But, to have this steady drumbeat of chaos and confrontation coming out of the American South … was problematic.”

A “Daughter of Selma” Fighting to Remove Today’s “Bad Actors”

“As a daughter of Alabama and representative of Birmingham, Selma, and Tuscaloosa and Montgomery, there is not a time when I didn’t remember ‘Bloody Sunday’ and the commitment of the foot soldiers that fought for equal rights to vote for everyone,” said Rep. Terri Sewell (D-Ala.), the state’s first black woman elected to Congress. “I never would have imagined that their cause would become my cause.”

Her cause is the passage of H.R. 4, a bill to restore the voting rights protections that were stripped from the 1965 Voting Rights Act when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2013 that a section on preclearance was unconstitutional.

At issue in Shelby County v. Holder was the legality of Section 5, which requires certain states to get federal approval — or “preclearance” — before changing their voting laws or practices, and Section 4(b), which outlines the formula that determines which jurisdictions are subject to preclearance based on their history of discrimination.

While upholding Section 5, the court struck down Section 4(b) on the grounds that the formula was based on data more than 40 years old. Without a new formula, no jurisdiction can be subject to preclearance.

In the years since, jurisdictions previously subject to preclearance have increased voter purges, closed polling sites in predominantly black counties, and curtailed early and mail-in voting.

Rep. Sewell is now conducting evidentiary and field hearings to establish a more equitable formula.

“I look forward to working with Congress to let the world know there are bad actors out there instituting voter suppression laws,” she said. “There is nothing more basic than being engaged in the electoral process.”

This year’s “Bloody Sunday” is bittersweet for Rep. Sewell. As she has done for many years, she returned to her church — Brown Chapel A.M.E. — for a commemoration of that violent day in March 1965, but it will be different due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic and the absence of John Lewis.

“This will be the first time in my life commemorating the events of Bloody Sunday, via a drive-through march, without John Lewis,” Sewell said. “But, as beneficiaries of his call to action to keep the faith and exercise our moral obligation to do something, we must pick up the baton toward forming a more perfect union.”

(Edited by Kristen Butler and Alex Patrick)

The post Remembering Selma’s ‘Bloody Sunday’ And The Fight For The Voting Rights Act appeared first on Zenger News.