A Florida appeals court upheld Gov. Ron DeSantis’ congressional redistricting map, finding a lower state court should have dismissed a lawsuit challenging North Florida’s districts.

Even though DeSantis’ lawyers admitted his map violated the state constitution by diminishing Black voting power, the First District Court of Appeal said state voting protections shouldn’t apply to a Jacksonville-to-Tallahassee congressional district ordered by the Florida Supreme Court last decade.

Even though DeSantis’ lawyers admitted his map violated the state constitution by diminishing Black voting power, the First District Court of Appeal said state voting protections shouldn’t apply to a Jacksonville-to-Tallahassee congressional district ordered by the Florida Supreme Court last decade.

The plaintiffs have already filed an appeal to the Florida Supreme Court. The state’s highest court is not required to take up the case.

In 2021, DeSantis vetoed an earlier attempt by the Florida Legislature to comply with anti-gerrymandering protections in the state constitution, arguing one of those protections, the “non-diminishment” clause, violated the U.S. Constitution by protecting Black voters’ ability to elect candidates of their choice.

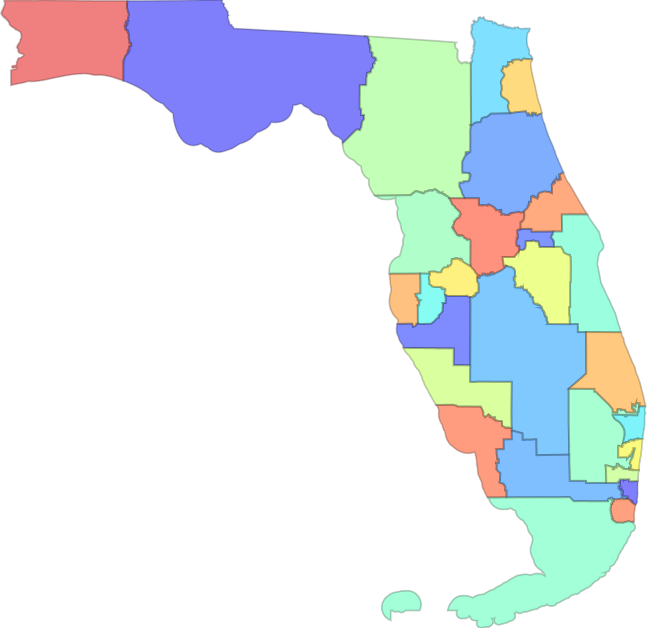

Instead, he replaced the map with one of his own, which created whiter, more Republican districts in North Florida.

Friday’s decision was eight-to-two in favor of upholding DeSantis’ contested districts and striking down the lower court decision. Three judges recused.

This means the governor’s map, which resulted in all Republican congressional districts in North Florida, will remain in effect for 2024 — unless the Florida Supreme Court or a separate federal lawsuit strikes them down. Both the state and federal lawsuits only challenged North Florida’s districts.

The new ruling went so far as to say two of last decade’s Supreme Court rulings should not be considered binding precedent.

Jacksonville Democratic state Sen. Tracie Davis said in a statement the redistricting process was “a disservice to the people of Jacksonville.”

“Protected districts were created to give minority voters the chance to have a representative that looks like them and represents their interests,” she said, “and that chance has been unceremoniously stripped by the Legislature and the courts.”

In 2010, 63 percent of Florida voters codified anti-gerrymandering protections into the state constitution as the Fair Districts Amendments. Parts of those protections included copied language from Section 2 and Section 5 of the federal Voting Rights Act.

Last decade, the Florida Supreme Court decided that it should apply those protections the same way they’re applied federally. The protections included a “non-diminishment” provision that barred the state from reducing the number of districts that allow voters from racial minority groups to elect their preferred candidates.

That, the 1st District Court of Appeal said, “simply makes no sense.” Because Florida’s constitutional language wasn’t as expansive as the federal Voting Rights Act — which included a requirement for some jurisdictions to preclear voting changes through the U.S. Department of Justice — the state shouldn’t apply the non-diminishment protection in the same way.

The Florida Supreme Court was wrong, the lower court said. Instead, the court decided the non-diminishment protection should be applied similarly to a separate, different provision from the Voting Rights Act, which requires a more difficult test before it can apply.

During oral arguments, First District Court of Appeal Judge Adam Tanenbaum, who was appointed to the appellate court by Gov. DeSantis, criticized the high court.

“It was acting in a political capacity when it’s drawing a district, which is the same as what the legislature typically would do,” he said of the Florida Supreme Court’s decisions last decade. “So why isn’t it fair to question what the Supreme Court did in a prior — when it was enacting or approving the enactment of a court-drawn set of districts?”

In a rare move, two judges — Tanenbaum and Judge Brad Thomas, appointed by former Gov. Jeb Bush — co-authored the court’s majority opinion. In all, seven judges signed on to the majority opinion, and an eighth agreed with its result.

Reached Friday, former Florida Supreme Court Justice Barbara Pariente, who authored those opinions, said, “I fear that the jurists who were acting politically were the members of the majority of the First District Court of Appeal.”

Michael Li, senior counsel for the Brennan Center‘s Democracy Program, said Florida’s appellate court misunderstood federal law.

The First District Court of Appeal decision relied on federal opinions that provided a test for proving illegal vote dilution — a separate claim from the vote diminishment that plaintiffs alleged. That test is harder to prove than the test the Florida Supreme Court laid out last decade for proving diminishment.

Among other things, that harder test requires plaintiffs to show it’s possible to draw a compact, majority-Black district. The Florida Supreme Court’s non-diminishment test didn’t require the district to be majority Black.

“If the court is purporting to follow federal law, it gets federal law wrong,” Li wrote in a message to The Tributary about the First District Court of Appeal’s decision. “In particular, it conflates what you have to show to compel [the] creation of a district under the VRA with the standards for measuring diminishment (retrogression) under section 5.”

Genesis Robinson, political director for Equal Ground, one of the plaintiffs in the case, said the new decision “sets a dangerous precedent for the erosion of voting rights in Florida.” Robinson said the plaintiffs would “continue to explore all of our options to stop the unchecked extremist power in our state and to protect the voting rights of all Floridians.”

Ellen Freidin, CEO of FairDistricts NOW and one of the leaders who championed the Fair Districts Amendments, criticized the ruling as undoing the gains made by those constitutional amendments.

“As part of this selfish effort to do away with fair voting, Ron DeSantis made it clear from the start that as governor, he would do anything to wipe out the Fair Districts Amendments,” Freidin said. “In urging this court to uphold his discriminatory and unconstitutional map, he erased the rights of hundreds of thousands of Black citizens to have their voices heard in Congress.”

Be the first to comment