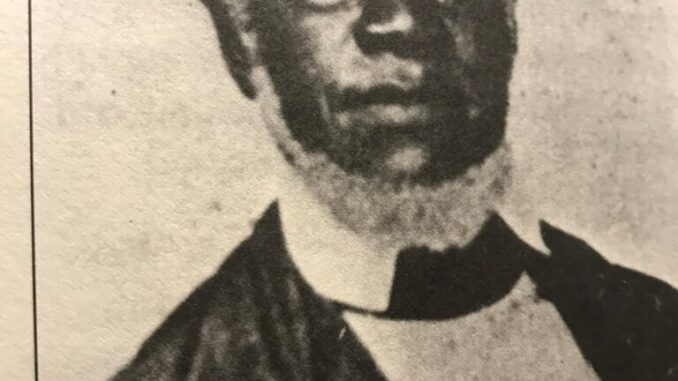

(Source: www.capitaloutlook.com) – By Valerie Scoon –FSU College of Motion Picture Arts –In his timely and very well researched book, “Father James Page: An Enslaved Preacher’s Climb to Freedom”, Dr. Larry Eugene Rivers, distinguished professor of history at Florida A&M University, recounts the life and powerful influence of one of Florida’s most prominent citizens.

Born into slavery in Richmond, Va., in 1808, Page was forced to walk from Richmond to Florida by his owner Col. John Parkhill. In the Second Great Forced Migration from the upper South to the lower South, Page and an estimated nearly one million other enslaved persons were often permanently separated from their families. Page literally watched as Parkhill sold his mother and brother to finance the trip to Florida.

Rivers thoughtfully acknowledges the complex relationship between Father Page and Parkhill, the man who had sold his mother. Despite the modern-day pressures to expect or demand more confrontation, Rivers uses Page’s letters and his post Emancipation interview to faithfully explain the inevitable daily compromises of life during slavery.

In his early life, Page became literate in order to help his owner Parkhill make money in his store. During slavery, Parkhill appointed Page as overseer of his cotton plantations. Rivers acknowledges Page’s “nervous ambivalence about whom he wanted to please: his master, his fellow slaves or his own self-interest. It proved a conundrum never fully resolved.”

By skillfully balancing these competing concerns, Page oversaw the production of cotton, secured the favor of his master and was allowed to pursue his personal calling of preaching. By obtaining permission from Parkhill, Page could travel around Florida and Georgia and other neighboring states spreading the gospel. Here again, Page had to convince skeptical enslaved persons that Christianity was for them and at the same time advocate to Whites that Black people even had souls.

While some of Page’s sermons spoke of freedom and salvation in the hereafter (as was often true of ministers at that time) Page was also focused on giving his flock some uplift and balm for their present lives.

“I wanted to teach my flock how to live while living on earth,” Page once said.

He encouraged his enslaved brethren to care for themselves and feed themselves to the extent they were able. Eventually, Page became a prolific Baptist preacher establishing over 100 churches throughout Florida and Georgia. His own church Bethel Baptist Missionary established in 1870 continues today almost a century and a half later.

Rivers insightfully recognizes that Page continued his dual faces of public accommodationist in the presence of Whites and his private affirmation of Black freedom before and after the Civil War. Reminiscent of W.E.B. Dubois’s “double consciousness,” Rivers invites us into the dual operating mind of the public and private persona of a Black leader in the times of slavery and thereafter. Also, reminiscent of Booker T. Washington, Page routinely looked to Whites for financial support to establish schools and churches and exhorted his flock to work and to build wealth within a framework that accommodated White concerns.

Rivers places Page fairly in the context of Reconstruction era politics. He and others assumed important leadership positions both as elected and appointed officials. One of Page’s contemporaries was Robert Meacham, a leader of the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the founder of Bethel AME church in Tallahassee. Meacham and Page while both in the Republican party of Lincoln, followed different paths in balancing the demands for immediate equality with access to White benefactors and wealth. Page often took a position less confrontational to White social concerns and more accepting of social segregation. Both men focused on the importance of education and worked to establish schools for the recently emancipated.

According to Rivers, Page was at once a “sexist, a segregationist, a moralist, a pluralist, a pragmatist, an overseer/manager and a conservative political leader.” Page never taught his wife of 50 years, Elizabeth, to read and he refused to recognize women in positions of religious authority. Still, Rivers keeps his narrative largely free from the tendency to judge a man’s life by modern day values or to second guess the survival strategies of enslaved persons.

Father Page died in Tallahassee in 1883. He was mourned by standing-room only services throughout Florida and even into Georgia. He was recognized then and now as an extremely significant figure. According to Rivers, Page’s most lasting legacy was his institution building in laying the foundation of Florida’s modern-day predominantly Black Baptist churches. Because the past informs the present, Rivers illuminates the path of Father James Page’s climb to freedom as a framework for measuring our own lives and the progress of Florida and America toward achieving racial justice and equality.

Be the first to comment