Many African American families possess a cache of generational travelogues, packed tight and out of sight. These reminiscences, shared sparingly, if at all, do not for a moment romanticize the adventures of the open road.

They are nothing short of horror stories: The great uncle threatened at gunpoint and run out of a segregated sundown town; the father who racked up hundreds of miles to keep moving and avoid the potential indignity — or fury — of being turned away from lodging.

In the opening pages of her meticulously examined history, “Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America,” Candacy Taylor relates one of her own family’s hard-won testimonials. It’s a memory so specific yet strikingly familiar.

Her stepfather Ron, then a child, rides in the back seat of the family car — a shiny, fully loaded 1953 Chevy sedan. When a sheriff orders his father to the side of the road, the day shifts from bliss to dread. The questions land fast: “Where did you get this vehicle? What are you doing here?”

The father’s answers, rehearsed and ready, are all fiction: It was his employer’s car, and he’s a hired driver. His wife is the employer’s maid.

“Where is your chauffeur’s cap?” the sheriff demands.

Ron’s father gestures to a hook above the backseat. “Until that day, Ron never paid attention to that cap,“ Taylor writes, “but now he realized that it wasn’t just any hat. It was a ruse, a prop — a lifesaver.”

During the Jim Crow era and beyond, travel for African Americans was frequently yoked to humiliation or terror. Black travelers knew that even a simple road trip required props and a plan. Part of that essential prep included “The Negro Travelers’ Green Book,” a travel guide first published in 1936.

Taylor’s new book revisits the nesting stories behind the “Green Book,” which helped black tourists navigate racial minefields implicit in a road trip — whether across counties or cross-country.

Distributed by mail order and sold by black-owned businesses, the “Green Book” listed black-owned (or black-friendly) hotels, tourist homes, restaurants, nightclubs, haberdasheries, hair salons, barbershops and attorneys’ offices. It afforded black travelers the “courage and security” to pass through unknown territory.

Publisher Victor Hugo Green, a black mail carrier in New York with a seventh-grade education, said he’d come to the idea while observing a Jewish friend consult a kosher guide to plan a vacation in the Catskills. Taylor, however, suspects a more complex origin story. Green, who also managed the career of his musician brother-in-law, had no doubt absorbed stories about the travails of securing safe accommodations on the road; those anecdotes would have been influential as well.

Green teamed up with fellow postal worker George I. Smith to create the guide. “The first edition was only ten pages,” writes Taylor, “but it was a mighty weapon in the face of segregation.” Green’s brother, William, later joined Victor and his wife, Alma, to produce the guide out of their Harlem home.

At the outset, 80% of the listings were clustered in traditionally African American communities, including Harlem, Chicago’s Bronzeville and Los Angeles’ black enclaves stipulated by racial housing covenants and held in place for decades by redlining. The “Green Book” became a trusted brand and an emotional touchstone due to Green’s vision, grit and stamina and the guide’s consistency and reliability.

Taylor assiduously retraces the “Green Book’s” history, from 1936 to 1967, and the Denver-based writer and photographer embarked on her own cross-country road trip seeking what remains. This was a grueling, faith-testing journey of loss and heartbreak that enlarges and shapes her book’s vision. After three years of scouting nearly 5,000 locations named in the guide, she learned that fewer than 5% are still in operation. Many of the early buildings in black communities have vanished, about 75%, she reports, “destroyed in the name of urban renewal.”

In scope and tone, “Overground Railroad” recalls Isabel Wilkerson’s “The Warmth of Other Suns,” which explored the waves of the Great Migration as many African Americans moved during the 1900s from the rural South to Northeastern, Midwestern and Western cities.

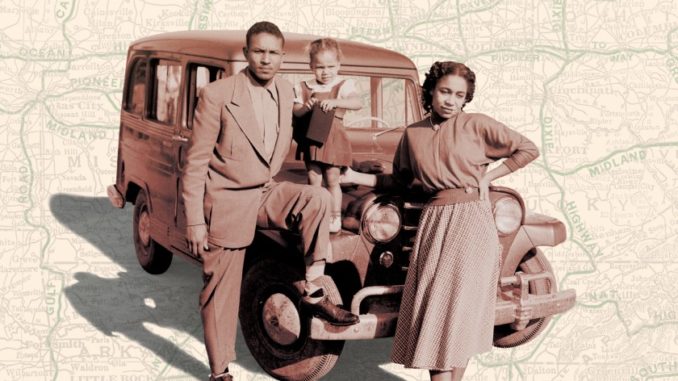

Taylor creates a vivid, multi-voiced travelogue, drawing on interviews, archival documents and newspaper accounts. Historic photographs provide context. Her contemporary images drawn from her travels — landscapes of boarded-up or graffiti-laced wastelands, empty vistas where sites once stood — also play a dynamic, before-and-after role in storytelling. At its center, the book is a nuanced commentary of how black bodies have been monitored, censured or violated, and it compellingly pulls readers into the current news cycle.

While “Overground Railroad” honors Green’s prescience within the context of the country’s cycles of racism, Taylor asserts that the “Green Book” was never overtly political. It did, however, provide an alternative approach to creating a resilient social network. In this, Green’s dream provided a way to work within the system, to manifest one’s own aspirations.

Taylor draws a compelling map connecting the legacy of institutional racism — decades of government disinvestment, redlining and the fight for adequate schools — that has left neighborhoods as discards or afterthoughts. She advocates for readers to use these stories as inspiration to actively build on the foundation Green laid.

The “Green Book” was never a money-making venture. “The reward was so much more valuable than money,” Taylor writes, “because [with] every business listed he may have saved a life.”

Be the first to comment