by Tiffany Pennamon

The vital role and relevance of historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) has been contested in contemporary times. Until recently, no central text or film documented the history of these institutions as they transformed the lives of African-Americans and American society over the arc of time.

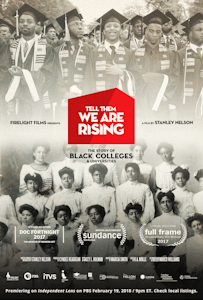

Emmy award-winning director Stanley Nelson’s forthcoming film does just that. Grounded in history, “Tell Them We Are Rising: The Story of Black Colleges and Universities” sheds light on the “unapologetic Black spaces” specifically dedicated to affirming Black students’ identities, culture and intellectual possibilities.

“The thing I love most about this film is that it drives home the fact that education has always been at the center of the Black freedom struggle,” says Dr. Crystal R. Sanders, associate professor of history and African-American studies at Pennsylvania State University. “Before and after emancipation, African-Americans pooled their resources to set up institutions of learning because they understood that literacy was the key to freedom itself.”

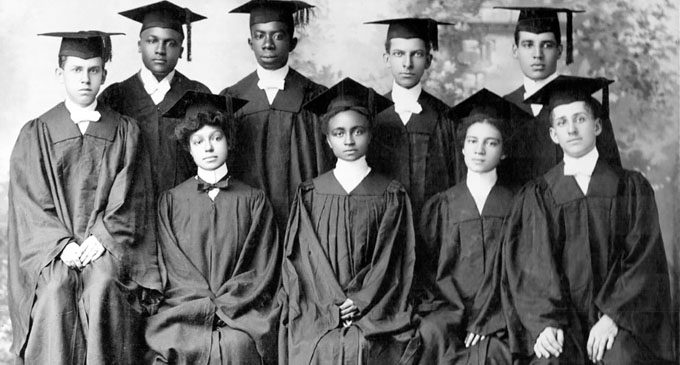

Beautiful black-and-white archival images of freed Blacks with heads down in books, gathering at schoolhouses and taking education into their own hands, is at the beginning of the narrative Nelson weaves about the nation’s 100-plus HBCUs. The inclusion of speeches by Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Du Bois and other key Black intellectuals shows the sharp divide in early theories on how to promote Black social and economic progress at the turn of the 20th century.

Dr. Marybeth Gasman, director of the Penn Center for Minority Serving Institutions and the Judy & Howard Berkowitz Professor of Education at the University of Pennsylvania, says she appreciated Nelson’s inclusion of rich voices, institutional archival material, music, color and sounds throughout the film — sounds such as those of Florida A&M University’s “Marching 100” band, church choirs and students’ freedom songs of the protest movements in the 1950s and ’60s.

A historian by training, Gasman says the inclusion of African-American scholars and historians was especially noteworthy to her. Viewers can expect to see scholars, historians and Black education leaders like Sanders, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Margaret Washington, Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole, Dr. Heather Andrea Williams, Dr. Jonathan Holloway and Johnny C. Taylor — formerly of the Thurgood Marshall College Fund — curating the history of HBCUs at different points throughout the film.

The African-American historians featured in the film are scholars whom viewers “don’t get to see in documentaries” because they are often overlooked, Gasman said. “To me, that’s incredibly important.”

Realizing that the film’s audience would include people who do not know much about HBCUs as well as those who have continued family legacies at HBCUs, Nelson says his production team’s attempt was to appeal to everyone by crafting a story about what HBCUs stand for and what they’ve meant to African-Americans.

“The research process was a lot harder than I thought it would be because there is no real central text about HBCUs,” Nelson says. “So a lot of it was using a piece from this book, a piece from that book … talking to consultants, advisers and other people and trying to piece the story together.

Gasman adds, “It’s surprising that a film like this hasn’t really been done before for PBS.”

Given the number of HBCUs in existence, Nelson says he could not tell every single story. Still, producers sought to include at least one image from every Black college in the film. By capturing key moments in HBCU history through seven or eight snapshot stories, viewers glean the powerful impact Black colleges had in developing Black leaders.

“Tell Them We Are Rising highlights that Black colleges were not created to simply give students knowledge “for the sake of [them] having it,” but for students to go on and do something concrete with that knowledge and the values invested in them by Black professors and peers.

From student protests at Fisk University in 1924 to school desegregation and reform efforts by Charles Hamilton Houston and Thurgood Marshall at Howard Law School in the 1950s to civil rights era sit-ins by North Carolina A&T and Bennett students in the 1960s, Nelson shows how Black college students fought not only for quality education and basic civil rights, but for representation in college leadership and in the board of trustees at many institutions.

Even for those who know a lot about HBCUs, “there’s so much there that you’re not going to know,” Nelson says. Additional montages of protests by students at Howard University, Morehouse College and other institutions give meaning to the film’s underlying message of struggle and resistance. Especially moving is the 1972 tragedy at Southern University, as clashes between students, administrators and state police resulted in two students’ deaths.

“The movie really enhanced the memories I’ve made so far and really helped me look at [HBCUs] in a different way,” says Brandon Langley, a freshman at Shaw University, an HBCU in Raleigh, N.C. “I see how hard they fought for HBCUs back in the day. They paved the way for us to come here and get an education in this time period. They did a lot of work back then for us now.”

Throughout the film, HBCU graduates — many of them student leaders and participants at the scenes of historical events — tell their compelling stories about the moments that enshrined them in history.

“I think Nelson’s film is the first film that I know of that shows the importance of developing Black leadership in these institutions,” says Dr. Raymond Winbush, research professor and director of the Institute for Urban Research at Morgan State University.

Referencing Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Kwame Nkrumah, Julian Bond and Toni Morrison as examples of the numerous leaders produced by HBCUs, Winbush says he learned even more about the types of graduates produced by Black colleges after viewing the film.

While “Tell Them We Are Rising” is a comprehensive overview of HBCU history, Sanders of Penn State says it is a teaser. So far, a screening tour at college campuses of the documentary, which has received financial support from the Lumina Foundation, has continued the dialogue about the history and cultural role of these institutions.

At a recent screening at Howard University, students, alumni and guests waved, clapped and shouted proudly when they saw their respective schools on screen. Performances by Howard’s “Marching Bison” and vocal jazz ensemble group “Afro Blue” captured the essence and unity of the Black college experience before and after the film viewing.

Similarly, at a screening held at Shaw, the birthplace of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), guests heard directly from Nelson and were treated to a performance of “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” by gospel sensation Shirley Caesar, also an HBCU alum.

During Q&A portions at the screenings, attendees voiced a desire for a sequel to the documentary, or even a mini-series. They also urged HBCU graduates to financially support Black colleges to ensure their continuation. But, particularly, they hoped people would no longer question the need for HBCUs after the release of Nelson’s film.

Nelson, who received national acclaim for his 1999 documentary about the Black Press called Soldiers Without Swords, adds that a combination of social and political events, like police violence and protests on campuses, is making young Black people say, “‘Let me look at a place where I’m going to be safe; where I’m going to be free; where I’m going to have this safe intellectual space for four years of my life. … For once, just for four years, let me live without this stigma of race coloring every single thing I do.’”

In January, the director made an Op-Doc for The New York Times titled “Black Colleges in the Age of Trump,” with the hope of continuing the conversation about the relevance of Black colleges in today’s contentious political era.

“It’s films like this that the administration doesn’t want you to see,” he told the audience at Howard’s film screening. “Tell a friend to tell a friend” to watch, he encouraged them.

The documentary will premiere on “Independent Lens” on PBS, Feb. 19 at 9 p.m. EST (local WJCT Channel 7).

“What we hope that the film does is just allow young people to take a look at HBCUs and make a choice,” Nelson says. “I’m not saying that HBCUs are for everybody, but I’m saying that as you think about your life and what your life is ahead … HBCUs [should] come into consideration, and then you make that choice.”

Be the first to comment