By Dwight Brown – via DwightBrownInk.com. Those who can, teach. Those who can’t, but want their narrative told anyway, try satire.

Somewhere in the basic code of screenwriting is a mantra that says, “Show don’t tell.” If you have a message, and you dispense it visually, audiences are smart enough to follow it and see the point. And if they watch and learn a lesson on their own—they become knowledgeable and feel empowered. Bludgeoning viewers with a message is pedantic. Counterproductive. Case in point.

Writer/director Kobi Libii has decided to give credence to a trope about Blacks being subservient by nature, on demand or by bad circumstance. He ups that ill notion by creating a group of Black folks whose mission is to make white people feel comfortable. Like Mammy, played by actress Hattie McDaniel, did in Gone With the Wind. Or like actor Lincoln Perry did when he rode his Stepin Fetchit Uncle Tom persona to fame and fortune. You get the picture? McDaniel’s fawning, amiable mammy figure is one white audiences love—even now. What Perry left behind is an image of clownish submissiveness that is as rueful today as it was yesterday. It’s a self-defeating persona that’s been banished from public display for a long time, until this ill-conceived production.

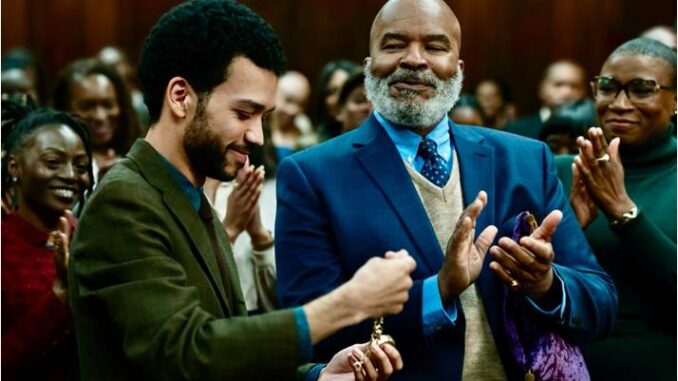

The script’s poorly thought-out premise and stretched-thin-plotline centers on Aren (Justice Smith), a visual artist and yarn sculptor, whose exhibition in a white woman’s gallery is not going well. Some potential white customers think he is a busboy and not an artist. Aren plays into the patronizing and dehumanizing view of himself—ad nauseum. Roger (David Allen Grier) observes the young man’s backpedaling, side-stepping, shuffling and cowardly behavior. “Watching you walk through a room full of white people was the most painful thing I’ve ever seen.” For Roger, Aren is a prime candidate for joining his secret society of Black folks who love tending to white people’s needs.

If this setup repulses you, that is largely the point. Aren feels like he has been beholden to whites and their whims for so long it’s become ingrained. When he discovers that behavior has been codified—by Black people like him—he is appalled. Then intrigued. Then slowly fights his way out of a hell of his own making. Note that the film adds touches of “magical” time and place travel, but that special effect is about as enthralling as card tricks at a three-year-old’s birthday party.

The director has a background in short filmmaking, but decided this parable should be a 1h 44m film (editor Brian Scott Olds). Clearly the writing and direction are out of the long-movie league. Nothing in this storyline, with its shallow characters and weak plot devices, cries out “Make me a feature film.” As a protagonist Aren is not relatable. In fact, he’s whiny and annoying. Not irritating enough to be funny. More annoying like a Black Woody Allen. Someone who has no friends because people find him abhorrent.

As Wren wrestles with his identity, or lack thereof, none of his trials and tribulations resonate. He’s working for the tech startup MeetBox, run by Mick (Rupert Friend), a generic startup leader. His competition for attention at the office is Jason (Drew Taylor). His competition for Lizzie (An-Li Bogan), a young woman he fancies who works at the same company, is also Jason. Even with his work colleague as a rival, the real antagonist is in Aren’s head. It’s him. It’s hard for audiences to hate an enemy they can’t see. That’s why they’ll sit on their empathy and compassion and not give any to the lead character.

Before filmmakers make a movie, they need to consider who their audience will be. Or if there is an audience for their work. Or if their film has a lane—or can create a new one. Any Black person with an ounce of self-respect will be uncomfortable with the film’s title, repulsed by the subject matter and annoyed that images of African Americans with no self-esteem are still being laid on the general public, like it’s a thing. If building a backbone is an issue for anyone of African heritage, their time is better spent with a psychologist, a Black Studies professor or listening to hip-hop or rap music. Those artists, and their generation, aren’t lacking self-confidence or awed by Caucasians. Those are better “teaching” options than this drivel.

As indie films go, these actors don’t stand out from the fray. Friend and Taylor fall in that category. Grier as the guide, Aisha Hinds (TV’s Underground) as the teacher and Nicole Byer as the leader of TASOMN waste their talent too. But Bogan shows a gift for modern, rom/com and gives one of the few performances that doesn’t seem forced. Her moments with Smith lift him up. His moments without her are in a dead zone. And if their comic, interracial, multi-cultural romance is the film’s only strong suit, what’s the point?

Reviving old stereotypes, pinning Black people to inferiority complexes and making all whites insensitive devils seems passé. And certainly, in this case there isn’t a suitable payoff for being assaulted by microaggressions and degradation for over 90 minutes. That’s the price anyone will pay for watching feeble, bombastic satire—which isn’t funny.

Even if this misguided film was a twenty-minute short, it would still be twenty-minutes too long.

Trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gizIbhk5Eu4

Visit Film Critic Dwight Brown at DwightBrownInk.com.

Be the first to comment