This palpable emotion – ranging from distress to defiance — is expressed in 48 personal letters from Black mothers to America that comprise the book “boy,” also known as “Defending Our Black Sons’ Identity in America.” The book also is commonly referred to as “The Boy Book.”

“I was just thinking…”

By Norma Adams-Wade, Founding Member of the National Association of Black Journalist, Texas Metro News Columnist

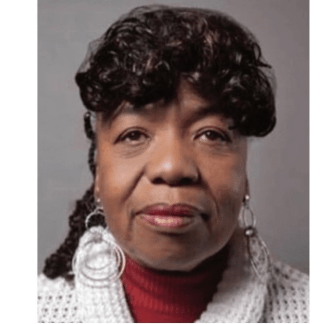

Eric Garner’s mother Gwen Carr knows paralyzing grief first-hand. Other Black mothers across the nation say they share a similar mind-numbing foreboding: the possibility of fear or hatred of Black people by police or racists killing their Black sons.

Gwen Carr, mother of Eric Garner, Credit: MTE Publishing

This palpable emotion – ranging from distress to defiance — is expressed in 48 personal letters from Black mothers to America that comprise the book “boy,” also known as “Defending Our Black Sons’ Identity in America.” The book also is commonly referred to as “The Boy Book.”

Images of watching media reports of the May 25, 2020 murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer would not allow her to rest until she completed the boy. book that she views as a catalyst for change in America.

The book also includes chapters about (a) what your rights are and how to act if stopped by police, (b) a historical perspective about treatment of Black men and women by police, and (c) a licensed mental health counselor’s assessment of lingering trauma from police brutality and/or racist treatment in various settings.

Cover of book “boy.” Credit: Sherilyn Bennett

“We must recognize that not all fights against racial inequality happen in the streets,” Bennett said in a promotional piece.

Bennett, Eric Garner’s mother Gwen Carr, and a couple of the mothers who wrote essay letters will be in Dallas this month for a book signing, meet and greet, and to encourage other mothers who have experienced or are experiencing similar traumas of losing sons in police or racist encounters. The signing will be from noon to 3 p.m. June 12 at Pan-African Connection, 4466 S. Marsalis Ave. in Dallas.

Gwen Carr, Eric Garner’s mother wrote the book’s Foreword. Some of Garner’s last words, “I can’t breathe,” became a national rallying cry after the 43-year-old, 6-foot-3, 350-pound, great-grandfather[cq of six died July 17, 2014. He had several existing health problems including severe asthma.

Video recordings show that Garner repeated “I can’t breathe”11 times while Daniel Pantaleo, a White New York police officer, used a chokehold, already illegal at the time, while arresting Garner. Authorities say the police suspected Garner was selling cigarettes illegally on the street in Staten Island. The medical examiner ruled the death a homicide, but a Richmond County grand jury refused to indict the officer who was acquitted.

New York City later reached a $5.9 million out-of-court settlement with Garner’s family. Five years later, the Justice Department refused to bring criminal charges against the officer but under a New York Police Department disciplinary hearing, Officer Pantaleo finally was fired in August 2019. Garner’s mother said the five-year ordeal transformed her. She now pushes for legislation beyond street protests.

“I chose to be a catalyst for change because I refused to be a culprit of complacency,” Carr wrote in the Foreword. “I transitioned from mourning to movement and from sorrow to strategy! …Eric’s name is one of too many names belonging to Black males that have been murdered by police officers who were acquitted.”

Rhonda Willis of Fort Worth wrote one of the letters. Her husband Fred Willis is helping promote the book. She tells of their son Joshua, now 11, earlier in grade school when a White classmate told her son that he (the White student) was better than her Black son. When her son shared the story, she said she and her husband immediately began to regularly affirm their son’s worth to counteract any possible damage to his self-esteem.

“I used to think that racism didn’t start until boys were teenagers or young men but this really opened by eyes…,” she wrote in her letter.

Besides the book signing, the book also is available through Amazon and at some major retail book departments including walmart.com. To learn more, visit www.boybooknation.com.

Norma Adams-Wade, is a proud Dallas native, University of Texas at Austin journalism graduate and retired Dallas Morning News senior staff writer. She is a founder of the National Association of Black Journalists and was its first southwest regional director. She became The News’ first Black full-time reporter in 1974.

norma_ adams_wade@yahoo.com

Samplings from the 48 letters:

Compiling author Sherilyn Bennett, Credit: Sherilyn Bennett

- This one tells how an adult Black son politely held a restaurant door open for an elderly White man who arrogantly responded, “Thank you, boy.” The adult son felt insulted but did not retaliate.

- This one tells of university campus police who detained a Black male on campus saying he was not a student. The football coach finally verified him as a member of the team.

- Another titled “Mother Grizzly’s Letter to America” tells of her anguish following the 2012 killing of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin by a neighborhood watchman as the youth walked to his dad’s house carrying a bag of Skittles candy.

- This one details a 10-year-old son who has a 4.0 average in gifted classes; yet the mother worries that “Several studies prove the more educated… articulately vocal a Black male is, the more at risk he becomes to encounter injustices.”

- This one tells of having “the talk” with her sons, schooling them that “no amount of education, wealth, or accomplishment can fully shield them from being Black.”

- And this one: “Imagine feeling obligated to tell your sons: – Don’t drive certain cars or go certain places – Don’t put your hands in your pockets – Don’t put your hoodie on – Never leave the store without a receipt or a bog. – Never leave the house without your ID. – If you every get pulled over, put your hands on the dashboard and do not make any movements without asking. This is our existence. I wish that I did not have to have these talks with my Black sons.

Be the first to comment