BY RANDAL MAURICE JELKS SPECIAL TO THE STAR

“So if Dippy would go out to Kansas, there would be no trouble?” asks basketball legend Wilt Chamberlain’s mother in “Jayhawkers,” the independent film directed and co-written by Oscar winner and University of Kansas faculty member Kevin Willmott.

Phog Allen, Kansas’ legendary basketball coach, responds, “I can assure you he will feel right at home in Lawrence.” And he adds: “Miss Chamberlain, if Wilt can come to (the University of) Kansas, sure, he can win a national championship, but he will also be getting one of the finest educations in the country. I can personally assure he will get his four-year degree.”

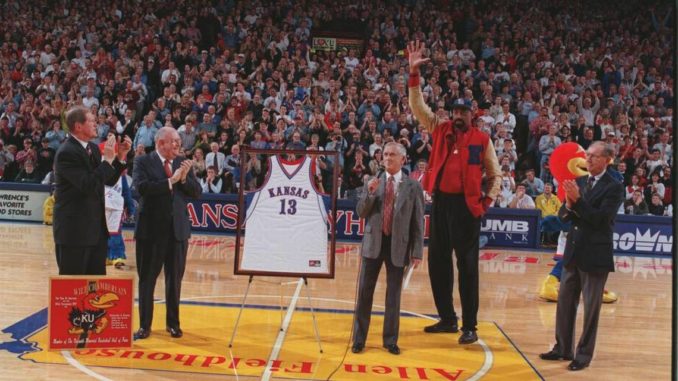

Like so many coaches are wont to do, Allen made his pitch in the Chamberlain home by convincing the player’s parents, and Chamberlain made his way to KU. But Allen’s salesmanship, as the film vividly demonstrates, was not completely accurate. Chamberlain wound up in the middle of the fight to integrate the city of Lawrence in 1955 in the aftermath of the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision.

Like so many athletes before and after him, Chamberlain thought that he was simply going to play ball and get a degree, without social realities invading the court.

The truth is American universities coveted black athleticism before they coveted black scholars. Black student-athletes continue to be dominant in basketball and football as collegiate athletics’ most televised athletes. And I am grateful for their visibility.

What I am not grateful for is how university athletic programs dissociate these highly recruited student-athletes from worldly realities outside their sport. Today, these high caliber players are carefully shielded from becoming fully engaged citizens.

It is rare for student-athletes to participate in a protest like the one University of Missouri football players joined in 2015. Rather, these students are cocooned inside a sports complex where coaches seek maximum control over them, expecting them to be nice volunteers, but not fully versed and critical thinkers. University of Virginia quarterback Bryce Perkins made himself an exception in collegiate sports, when he recently gave a shout-out to his gender studies professor for the important lessons she had taught him.

Coaches are not to be faulted solely for this disturbing situation. Top-level university administrators deserve more blame. They are the ones who oversee corporate deals. The branding deals are numerous, and most of these deals do not offer academic units that instruct these student-athletes any resources.

When my department asks if a former successful athlete could lead an endowment campaign to empower black scholarship, we are given the silent treatment. Academic programs that engage black students on entrepreneurship, globalization, artistic expression, critical thinking and history are ignored by administrators who, in the main, are white. Like coaches, they seek maximum control over black celebrity. For them, black athletes are entertainers for rich donors. In many ways, these sports-driven universities behave similar to nondemocratic state leaders who indefensibly attempt to limit citizens’ knowledge.

This was on full display when KU Athletics recently invited rapper Snoop Dogg on campus. Snoop’s show was a hip-hop set backed by a corporate sponsor. But unlike black student-athletes, Snoop gets paid in full. University administrators found the show embarrassing because it was not appropriate for all age groups. Sadly, but somewhat amusingly, they never consulted with anyone who studies hip-hop on campus. What is even more ominous, though, is that university officials rarely negotiate with corporate sponsors to contribute to academic endowments that focus on studying the genius of black life that also includes sports.

Phog Allen’s statement that Chamberlain would “also be getting one of the finest educations in the country” is simply not true today. Without aggressive investments combining both public and private endowments to support the humanities that study black Americans, Allen’s appeal will always be patently false.

Randal Maurice Jelks is professor of African and African American Studies and American Studies at the University of Kansas. He is co-editor of the journal American Studies.

Be the first to comment