BY A VIDEO SHOWS George Floyd, a black man, lying in the street in anguish, with his head crushed against the pavement. A white officer presses his knee into Floyd’s neck. “I can’t breathe,” Floyd, 46, says repeatedly. “Please. Please. Please. I can’t breathe. Please, man.” Bystanders, filming the scene, plead with the officer to stop. He doesn’t. As three other officers stand by, he kneels on Floyd for eight minutes and 48 seconds as the life seeps from his body.

“It was a modern-day lynching,” said Arica Coleman, an historian, cultural critic, and author.

“This man was lying helplessly on the ground. He’s subdued. There’s the cop kneeling on his neck. This man is pleading for his life. To me, that is the ultimate display of power of one human being over another. Historically, you could be lynched for anything.”

From 1877 to 1950, more than 4,400 black men, women, and children were lynched by white mobs, according to the Equal Justice Initiative. Black people were shot, skinned, burned alive, bludgeoned, and hanged from trees. Lynchings were often conducted within sight of the institutions of justice, on the lawns of courthouses. Some historians say the violence against thousands of black people who were lynched after the Civil War is the precursor to the vigilante attacks and abusive police tactics still used against black people today, usually with impunity.

Floyd’s death came six weeks after police in Louisville, Kentucky, fatally shot Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old black woman, during a midnight “no-knock” raid on her home. It came 10 weeks after the killing of Ahmaud Arbery, a 25-year-old black man, who was chased down by a white father and son in a pickup truck as he jogged in his neighborhood in Glynn County, Georgia.

Historians say the deaths seemed to rip the scab from 400 years of oppression of black people. During a pandemic that has disproportionately sickened and killed African Americans, the deaths unleashed a rage against oppression that became a catalyst for uprisings across the country and around the world—from Paris to Sydney, Australia; from Amsterdam to Cape Town, South Africa—as thousands poured into streets, demanding justice and an end to police brutality.

Bryan Stevenson, founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit that tries to address the nation’s racist legacy through activism and education, said the roots of the protests lie in the reality that the country has not yet come to terms with its brutal history of slavery, lynching, and continued oppression of black people.

“We have never confronted our nation’s greatest burden following two centuries of enslaving black people, which is the fiction that black people are not fully evolved and are less human, less worthy, and less deserving than white people,” Stevenson said.

“This notion of white supremacy is what fueled a century of racial violence against black people, thousands of lynchings, mass killings, and a presumption of dangerousness and guilt that persists to this day,” Stevenson continued. “So when Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor or George Floyd are killed, the immediate instinct of police, prosecutors, and too many elected officials is to protect the white people involved. Video recordings complicate that strategy, but even graphic violence caught on tape will be insufficient to overcome the long and enduring refusal to reckon with our nation’s history of racial injustice.”

Murdered in public view

In the aftermath of Floyd’s death, people openly wept and mourned after witnessing the video. For many, it was a reminder of the brutality that blacks faced historically.

In Boston, the president of Emerson College wrote an unprecedented letter to students, explaining his gut-wrenching reaction to Floyd’s slaying on camera and beginning, “Today, I write to you as a Black man … There is no other way to write to you, given recent events.”

“I didn’t sleep Friday night,” wrote Lee Pelton, a nationally known speaker on liberal arts education and diversity. “Instead, I spent the night, like a moth drawn to a flame, looking again and again at the video of George Floyd’s murder at the hands of a Minneapolis white police officer. It was a legalized lynching.”

Even as the country pursued an unprecedented effort to enforce social distancing to end a pandemic, he said, “it could not stop a black man from being murdered in public view.” Pelton wrote that he was struck by the “callousness and the casual dehumanization” of Floyd, as the officer nonchalantly continued to press his knee into Floyd’s neck.

A Minneapolis medical examiner ruled Floyd’s death was a homicide, explaining that his heart stopped as the officer compressed his neck. The officer, Derek Chauvin, was fired and later charged with second-degree murder. Three other officers on the scene were also fired and charged with aiding and abetting murder.

“To that officer, he was invisible—the Invisible Man that Ralph Ellison described in his novel by the same name,” wrote Pelton, who began his academic career as a professor of English and American literature. “Black Americans are invisible to most of white America. We live in the shadows.”

‘Dehumanization’ links these killings

That “dehumanization” of black people is a common thread in the recent incidents, historians say. It connects the untimely deaths of Floyd, Taylor, and Arbery—and the “weaponized” threat of a call to police against a black man who was bird watching in Central Park—to an ugly history of racial oppression in the United States and its horrible legacy of lynching.

Floyd’s death came the same week as Christian Cooper, a Harvard-educated board member of the New York City Audubon Society, was out observing birds in the forested Ramble section of the park when he encountered a white woman walking her dog off a leash.

When he asked the woman, later identified as Amy Cooper, to leash her dog in an area that requires dogs to be leashed, she refused. Christian Cooper began to film their encounter, as she warned she would call the police and report that “an African-American man” was threatening her. Christian Cooper, who calmly continued filming the call, explained later to The Washington Post, “I’m not going to participate in my own dehumanization.”

“It doesn’t make a difference what you do, whether you are bird-watching, selling water on the sidewalk or reporting the news, your very presence signifies a threat because of the meanings associated with blackness—dangerous, impurity, inhumanity, criminal,” Coleman said.

“Breathing while black” is the crime, Coleman said. “And that goes back to the history of the country. So many black people were lynched just for being black. It gives white people power, which is why that woman, Amy, knew the exact role to play—the white damsel in distress being threatened by the big, bad, black wolf. ‘I’m going to call the cops and tell them there is an African-American man threatening my life.’ She knew the script.”

Not only lynched, but tortured

In 2018, the Equal Justice Initiative opened the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, the country’s first memorial to the victims of lynching. The memorial contains 801 six-foot monuments constructed of oxidized steel, one for each county where a lynching took place. Each victim’s name is engraved on the rust-colored columns, strung from beams, much like the lynched bodies of black men, women and children who were likened to “strange fruit” in a 1930s anti-lynching protest song made famous by Billie Holliday.

Lynchings were a brutal form of extrajudicial killings and took place across the country, including the three states where Floyd, Taylor, and Arbrey lived. They not only included hanging people from trees, they often included torture. White mobs cut off black men’s genitals, severed fingers and toes, and skinned victims who were sometimes burned alive. Black women and children were victims too. According to records, white mobs sometimes sliced open the wombs of pregnant black women, killing their babies too.

The body of 32-year-old Rubin Stacy hangs from a tree in Fort Lauderdale, Florida on July 19, 1935. Stacy was lynched by a mob of masked men who seized him from the custody of

… PHOTOGRAPH BY ASSOCIATED PRESS

In 1918, Mary Turner, who was 21 and eight months pregnant, was lynched by a white mob in Southern Georgia after she protested the lynching of her husband the day before, according to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Walter White, who led the NAACP from 1929 to 1955, was sent to investigate. Between 1880 and 1968, there were at least 637 lynchings recorded in the state, according to a Tuskegee Institute study.

“Abusive plantation owner, Hampton Smith, was shot and killed,” according to the NAACP. “A week-long manhunt resulted in the killing of the husband of Mary Turner, Hayes Turner. Mary Turner denied that her husband had been involved in Smith’s killing, publicly opposed her husband’s murder, and threatened to have members of the mob arrested.”

The next day, a mob came after Mary Turner. “The mob tied her ankles, hung her upside down from a tree, doused her in gasoline and motor oil and set her on fire,” the NAACP reported. “Turner was still alive when a member of the mob split her abdomen open with a knife and her unborn child fell on the ground. The baby was stomped and crushed as it fell to the ground. Turner’s body was riddled with hundreds of bullets.”

Many of the black people lynched were never formally accused of crimes. Some were lynched simply for addressing a white person in a way the white person deemed inappropriate. Others were killed after being accused of bumping into a white woman, looking a white person directly in the eye or drinking from a white family’s well.

“There is a depth of hatred in the bone marrow of this country that supports the killing of the black body,” said CeLillianne Green, a historian, poet, and author.

The country was built on racial ideals of white supremacy, Green said. Forty of the 56 founders who signed the Declaration of Independence, as well as 10 of the first 12 presidents were slaveowners. The Constitution did not recognize black people as fully human, counting enslaved people as three-fifths of a free person.

White people were deputized to kill black people

Historians say the attitudes some white people held that black people were “inferior” spawned the racism behind current day oppression. That history includes slave codes passed by states that gave owners complete dominance over the lives of black people. Some states prohibited black people from gathering in groups, possessing their own food or learning to read.

Jim Crow and Black Codes laws were enacted to control the movement of black people at night. Some all-white towns enacted “sun-down laws,” which required black people to leave town by sunset. Many black people were lynched simply for “violating” these laws.

Lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abraham S. Smith, Marion, IN. 1930

… PROJECT BY KEN GONZALES-DAY

Lynching of Cleo Right, Sikeston, MO., 1942

… PROJECT BY KEN GONZALES-DAY

Lynching of Jesse Washington, Wako, TX., 1916

… PROJECT BY KEN GONZALES-DAY

The Wonder Gaze: Lynching of Thomas Thurmond & John Holmes, Saint James Park, San Jose, CA., 1933

… PROJECT BY KEN GONZALES-DAY

Lynching of Leo Frank, Atlanta, GA., 1915

… PROJECT BY KEN GONZALES-DAY

Lynching of Frank MacManus, Minneapolis, MN., 1882

… PROJECT BY KEN GONZALES-DAY

In the 18th century, Georgia required plantation owners and white employees to serve in the state militia, which enforced slavery, according to the ACLU. Throughout U.S. history, “white people were deputized to kill black people,” Green said. “The father and son in Georgia were acting like slave catchers.”

This scene is reminiscent of the violence that could result when enslaved black people were caught walking without the passes required by Black Codes.

A 30-minute cellphone video captured Arbery’s death on Feb. 23, as he jogged home. The footage shows him running down a street as two white men—later identified as Gregory McMichael, 64, and his son Travis McMichael, 34—waited to ambush him.

Arbery tries to fight them off before he is shot three times. He tries to run away but then falls in the street dead. It was two months before the men who killed him were arrested.

The slaying of Arbery does not exist in a vacuum, Coleman said. It comes from the history of “dehumanizing” black people. “All these incidents are connected by the fear of blackness.”

That “dehumanization” was legally reinforced in 1857, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Dred Scott v. Sandford that black Americans—whether considered free or enslaved—were not to be considered American citizens and could not sue in federal court. It meant the law did not protect black people, and “black people are not allowed to defend themselves,” Coleman said.

That concept came into play in the Taylor shooting, Coleman said, when police broke down her door in the middle of the night, and her boyfriend shot at them. “Not only did they shoot her eight times,” she said, “when her boyfriend who didn’t know what was going on tried to defend his home, they arrested him for attempted murder of a police officer because again black people are not supposed to defend themselves. That is the reality of black people from day one.”

Deadly accusations from white women

As protests exploded, the hashtag #AmyCooperIsARacist trended on Twitter. Social commentators said the Cooper incident reminded them of the danger to black men inherent in a white woman’s accusation to police, a reality that journalist Ida B. Wells documented in her research. This year, she won a posthumous Pulitzer Prize for courageous reporting on violence against blacks during the era of lynching.

Wells concluded that many black men had been lynched because of false accusations by white women. In a now-famous editorial published in her newspaper, Memphis Free Speech, on May 21, 1892, Wells wrote: “Nobody in this section of the country believes the old threadbare lie that Negro men rape white women. If Southern men are not careful, a conclusion might be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.”

Left: Mamie Till-Mobley, weeps at her son’s funeral on Sept. 6, 1955, in Chicago. Emmett Till, a 14-year-old visiting relatives in Mississippi, was murdered after he was accused of whistling at a white woman, Carolyn Bryant. Till was kidnapped in Money, Miss., on Aug. 28, 1955, tortured

…

Cooper’s threat brings to mind the most infamous false accusation by a white woman, the one that led to the killing of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old teenager from Chicago, who was lynched in Money, Mississippi, in 1955.

After being accused of whistling at a white woman, the teenager was kidnapped from his uncle’s home, tortured, and riddled with bullets. His body was wrapped in barbed wire attached to a 75-pound fan and then thrown in the Tallahatchie River. Several decades later, the woman who accused him of flirting with her admitted much of the story was a lie.

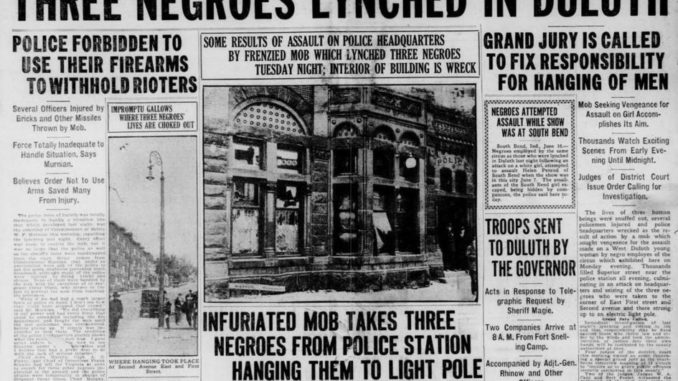

A similar accusation was made in 1920 against three black circus workers who were lynched in Duluth, Minn. Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie, who worked as cooks and laborers, had arrived in Duluth, only the day before with the John Robinson Circus.

“They were in town for a free street parade and one day of performances on June 14, 1920,” according to the Minnesota Historical Society.

That night, a 19-year-old woman named Irene Tusken and her friend James Sullivan, 18, attended the circus. “At the end of the evening the pair walked out the rear of the main tent,” according to the historical society’s account. “Nobody is sure of what happened next, but in the early morning of June 15th, Duluth Police Chief John Murphy received a call from James Sullivan’s father saying six black circus workers had held the pair at gunpoint and then raped Irene Tusken.” A physical exam found no evidence to substantiate the accusation.

Police arrested six black men. The newspapers reported the alleged assault and, by evening, a white mob “estimated between 1,000 and 10,000” gathered and forced its way into the police station. “They met little resistance from the police, who had been ordered not to use their guns,” according to the historical society. After a sham trial, Clayton, Jackson, and McGhie were declared guilty.

The men were tied to a light post, as shown in a photo that was made into a postcard, a grisly practice that lasted for some 50 years. In the image, two men hang by ropes from the pole, their shirts ripped open and their feet dangling, while another lies on the ground. A group of white men in topcoats and suit jackets, some smirking or smiling, surround the bodies.

‘Without the benefit of lawyers or courts’

Like Floyd, Taylor, and Arbery, many victims of lynchings were killed without due process, never charged with a crime, never offered an opportunity to mount a defense against allegations.

Seventy-four years ago, what’s known as the “Last Mass Lynching” occurred in Georgia, when a mob attacked two black men and their wives who were on their way from posting a bond.

On July 25, 1946, George W. Dorsey and his wife, Mae Murray Dorsey, and Roger Malcolm and his wife, Dorothy Malcolm were pulled from a car in Walton County, about 30 miles east of Atlanta, according to court reports. The couples were viciously flogged and tortured.

Two weeks before the attack, Roger Malcolm had been arrested and charged with stabbing a white farmer during a fight, according to an Equal Justice Initiative report. A white landowner for whom the Malcolms and the Dorseys worked as sharecroppers offered to drive them to the jail to post a $600 bond. But on the way back to the farm, a mob of 30 white men ambushed the car. The mob tied the four to an oak tree. Their bodies were riddled with bullets before the white mob cracked open their skulls and ripped apart their limbs, tearing their flesh.

The bodies were left hanging near the Moore’s Ford bridge, dangling above the Apalachee River, another gruesome scene in the American landscape of racism.

“They died without the benefit of lawyers or courts, stripped of all constitutional rights, and without a shred of mercy,” wrote historian Anthony Pitch, author of “The Last Lynching: How a Gruesome Mass Murder Rocked a Small Georgia Town.”

Ending evils like this

These lynchings also shocked the country, coming months after another horrific incident had sparked a national outcry. In Batesburg, S.C., a black World War II veteran in uniform was pulled from a bus after being accused of talking back to the driver. A police officer beat him unconscious and left him permanently blinded. Isaac Woodward had just received an honorable discharge. When President Harry S Truman learned that returning black veterans demanding their rights as citizens were being beaten, he said, “I shall fight to end evils like this.”

The slaying of the couples Moore’s Ford Bridge may have been the last recorded “mass lynching” in Georgia, but, despite Truman’s promise, lynchings continued across the country.

They were once so accepted that they were advertised in advance. Newspapers printed stories reporting the date, time, and locations of these planned extrajudicial executions. That may seem almost unimaginable now, but Coleman sees ugly similarities in today’s videos. “You had thousands of people get on trains,” she said. “Then they would put the images on postcards. Now, we have the internet and all this social media. I don’t see a difference. It becomes a murder pornography. You just sit there and watch somebody killed in real time.”

After the Emancipation Proclamation, when slavery was abolished, an era of racial terror followed, designed to keep black people subjugated to a white authority. “We had almost another century of indiscriminate violence against black people,” Coleman said, “because white supremacy does not see black people as free. And it’s still happening now.”

For more info visit: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/2020/06/history-of-lynching-violent-deaths-reflect-brutal-american-legacy/#close

Be the first to comment