By John Edwin Mason National Geographic – Sometimes one of the most interesting things about a photograph is what’s just outside the frame. That’s the case with the portrait of Deveonte Joseph that Nathan Aguirre made on a street corner in St. Paul, Minnesota a month ago during the protests after the murder of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, by Derek Chauvin, a white Minneapolis police officer. Across the street from where Joseph stood, barely outside of the camera’s view, is a building that connects him to another young Black man who lived in St. Paul nearly a century ago. The building is Gordon Parks High School. Its namesake was a man who, as a photojournalist, became one of the mid-20th century’s most influential interpreters of African American life and culture. The connection between Joseph and the school reveals much about the enduring nature of racial oppression in the United States and, at the same time, allows us to think about how that oppression and resistance to it have been represented in photography.

Deveonte Joseph

Joseph’s portrait, which I wrote about soon after Aguirre made it, captured the public’s imagination. It quickly went viral on social media and attracted the attention of mainstream news outlets such as CNN. It’s easy to see why. In the photograph, Joseph was incongruously dressed in an academic cap and gown, stylishly torn blue jeans, and basketball shoes, as if he were ready for both a graduation ceremony and the party afterward. Although he was isolated in the center of the frame, enough commotion was visible behind and to the sides of where he stands — men in riot gear, police cars, a large emergency vehicle of some sort — to suggest that a civil disturbance was nearby. Joseph’s outward calm belied the chaos that surrounded him. For many, the portrait symbolized a hopeful future for young Black Americans “as well as our failure to fulfill the promises we make to our youth,” as the writer Connie Wang put it.

The evening’s chaos was all too real. Protesters, angered by Floyd’s murder, took to the streets. Some smashed the windows of shops and other businesses and made off with merchandise. Arsonists, perhaps at the scene only to cause mayhem, set buildings on fire. The next day’s St. Paul Pioneer Press reported that 170 businesses were looted or burned on the evening of May 28 and the early morning of May 29. One of those “businesses” was Gordon Parks High School.

When I wrote about the portrait three weeks ago, I didn’t know that the school was so close nor that it had been damaged on that very night. These facts, as small as they are in the great scheme of things, are more than mere footnotes. Parks would have felt a kinship with Joseph despite the decades that separate their time in St. Paul. Both men struggled to finish high school (Parks never did), to climb out of poverty, and to live with dignity in a world where the odds were stacked against them. They also share a determination to transform the visual representation of African Americans—that is, to change what is said about them in pictures.

Joseph’s backstory is at least as compelling as his portrait. He comes from a large family and is the first among his siblings to graduate from high school. Getting to that point, he told Wang, was hard. “I’ve fought through it, but I did it,” he said. “I graduated.” It’s no surprise that Joseph struggled to finish school. The Minneapolis-St. Paul area has what one commentator has called some of the nation’s “greatest racial disparities in housing and income and education.”

Yet Joseph did graduate and was consciously making a statement when he put on his cap and gown on the evening that he was photographed. CNN reported that he dressed as he did because he wanted to challenge what he saw as the misrepresentation of African Americans. “People look at my people like we’re down, like we don’t have anything. I just don’t think we’re respected enough,” he told CNN. He is also someone with ambitious plans for the future. He told the St. Paul Pioneer Press that his dream after high school was to study animation in art school, although his inability to afford tuition payments might prevent it. (After his portrait went viral, friends established a fundraising campaign for him.)

St. Paul’s racial discrimination runs deep

All of this would have been familiar to Parks. Racial discrimination in St. Paul created barriers to education and upward mobility that he fought and eventually overcame. He moved to St. Paul, from his birthplace, Fort Scott, Kansas, as a 16-year-old after his mother’s death in 1928. Although his father sent him to the city to live with relatives, he found himself homeless and on his own after an argument with an older brother-in-law. For the next decade and a half, he bounced from one menial job to another. The racial discrimination in employment that he encountered in St. Paul prevented him from finding the economic security that would allow him to finish high school.

Although Parks would have seen a reflection of himself in the portrait of Joseph, he would also have understood the protesters who broke shop windows and carried away merchandise. He had been an angry young man. In his memoir, A Choice of Weapons, he acknowledged that “scalding experiences” with racism and white brutality in Kansas and Minnesota made him “quietly but dangerously violent.”

Parks did not remain so volatile, of course. His memoir traces the path that led him to choose “love, dignity, and hard work” as the weapons with which he would fight racism. But he wrote that he would always “recall the elaborate conspiracy of evil that once beckoned” him toward violence and an early death.

Parks’ anger connects him to the protesters who contributed to the chaos that surrounded Joseph when Aguirre made his portrait. In a recent the New Yorker article, Elizabeth Alexander refers to today’s young African Americans as the “Trayvon Generation.” This is the protesters’ generation and Joseph’s generation, one that has always understood the fragility of Black life in America.

Gordon Parks and Black Lives Matter

They knew that a white policeman or private citizen might kill them at almost any moment, with impunity. They had seen it happen to Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Sandra Bland, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and so many others. “They always knew these stories,” Alexander writes. The stories “instructed them that anti-Black hatred and violence were never far,” and they “were the ground soil of their rage.”

The Black cohort into which Parks was born possessed a similar knowledge. We can call them “the lynching generation.” Parks’ birth coincided with what Rayford Logan and later historians have called “the nadir of race relations.” This was the Jim Crow era of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when the position of Black people in American society was at its lowest point since the end of slavery and when lynchings were near their peak. African Americans were both segregated and terrorized.

The Equal Justice Initiative has counted more than 4,000 racial terror lynchings in the period between the end of Reconstruction, in 1877, and the dawn of the modern Civil Rights era in 1950. In Fort Scott, Parks’ birthplace, Jim Crow segregation was the abiding custom, if not the law. Lynchings were well known in the town and the surrounding Bourbon County. There were at least eight lynchings between the end of the Civil War and the 1930s, including one, in 1867, in which three Black men lost their lives. Another Black man was lynched in neighboring Crawford County, in 1920, when Parks was eight.

The incident made a deep impression on Parks. He wrote that he “would lie awake nights wondering if the whites had killed my cousin, praying that they hadn’t. … And my days were filled with fantasies in which I helped him escape imaginary white mobs.” These episodes were, as Alexander put it about the Trayvon Generation, “the ground soil” of his rage. And they would have given him insight into the psychology of the protesters who turned to violence.

Riots and racial injustice

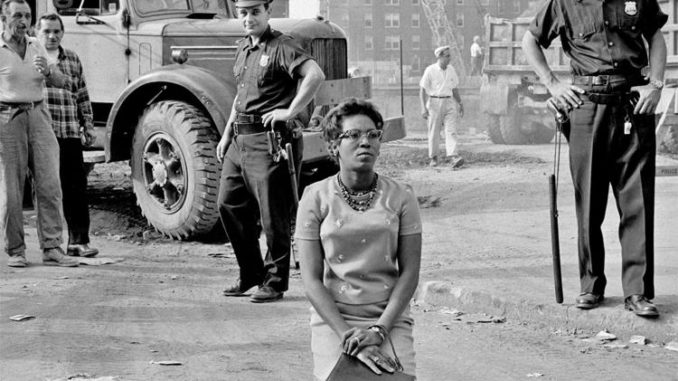

Parks learned to contain his anger and channel it into his work as a photographer, writer, and, decades later, a filmmaker. During the 20 years that he spent as the only African American on the staff at Life, he produced nearly a dozen lengthy photo essays that brought the reality of American racism home to the magazine’s millions of mostly white, mostly middle-class readers. He produced one of his most effective stories specifically to answer a question that he heard so often in the late 1960s: “Why are those people rioting?”

Parks knew, however, that photography has difficulty making structures of oppression visible. As he said in a 1983 interview, the camera could instead “expose the evils of racism, the evils of poverty… by showing the people who had suffered most under it.” So Parks answered the question “why?” by introducing his readers to members of a single impoverished family, the Fontenelles. He said that he wanted to show what their lives were like, “the real, vivid horror of it” and “the dignity of the people who manage, somehow, to live with it.”

This history essay can be read in its entirety in Nationalgeographic.com

Be the first to comment