Death is a recurring theme in Mexican culture. Mexicans have venerated it since pre-Hispanic times. Nezahualcóyotl, the ruler of the city-State of Texcoco in ancient Mexico, described life on earth as ephemeral and the attachment people have for it as a dream from which everyone eventually wakes up.

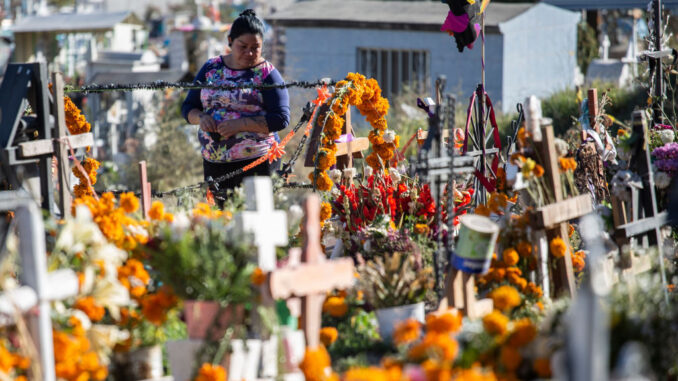

Today, Mexicans celebrate their dead ancestors with offerings where smells, flavors, and colors combine. Pan de Muerto (literally, the bread of the dead) and skulls are protagonists of these altars.

The origin of Pan de Muerto in México

During the pre-Hispanic period, the Aztecs or Mexica offered their god Tlalmatzincatl balls or figures made with a paste called tzoalli (amaranth, corn, and maguey sap.) Anthropologist Salvador Reyes Equiguas explains that given the sacred nature of tzoalli, Aztec ate these figures or balls “in the manner of communion.” The festival of Xocol Huetzi coincided with the current Day of the Dead celebration.

During this festivity, “a throne in the shape of a post was built, and several figures of gods made of tzoalli were placed on the crown. Young men would compete to see who could reach the top and grab the figures. Those who did offered the edible effigy to those who needed it among their family.”

During the colonial period, the Spaniards replaced tzoalli with anthropomorphic figures made of wheat bread, or molded-sugar faces, which gave rise to the Pan de Muerto, says anthropologist Marta Turok.

Some theories suggest that with the arrival of Catholicism, the Eucharist (the sacrament of receiving Christ’s body symbolized by a piece of bread) added a layer of meaning to the act of enjoying bread during the Day of the Dead.

Pan de Muerto is a bun with a round knob and decorations on top. It has a coat of sugar or sesame seeds. Pan de Muerto’s round shape symbolizes the circle of life. Its knob represents the skull of the deceased, while the decorative strips stand for their bones. Bakers often lace the strips (bones) forming a cross, alluding to the four cardinal points and the pre-Hispanic gods Quetzalcóatl, Tláloc, Xipe Tótec, and Tezcatlipoca. In Mexican culture, the native religion combined with Catholicism, creating syncretic expressions, such as Pan de Muerto.

Generally, Pan de Muerto has a base of flour, yeast, sugar, eggs, butter, and water. To evoke the memory of the deceased, bakers usually add orange blossom water to the dough. There are regional variations regarding the decoration and additional ingredients in the dough. For example, Oaxaca’s Pan de Muerto is a yolk bread decorated with alfeñique (sugar paste,) and Puebla’s bread has sesame seeds on top. Pan de Muerto’s preparation also accounts for its syncretic nature, as it combines the Spanish bread baking techniques and the Mexican natives’ vision of death.

Every year, Mexicans look forward to celebrating the Day of the Dead, on November 1 and 2. During the celebration, they enjoy Pan de Muerto with hot chocolate. UNESCO declared the Day of the Dead Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2003, recognizing this festivity that “holds great significance in the life of Mexico’s indigenous communities.”

(Translated and edited by Gabriela Olmos, edited by Ganesh Lakshman)

The post Pan de Muerto: A Sweet Mexican Tradition appeared first on Zenger News.