When Bronx native Luke Steele was released after more than two decades behind bars for an attempted kidnapping in the 1990s, he slowly but surely set about piecing his life back together.

Making good on his promise to the parole board that he was a reformed man, Steele, 55, soon landed a steady food-service job at New York University in Manhattan. He began rekindling relationships with his remaining family in the city, and eventually even got a girlfriend.

For about a year, things were looking up.

Then a bad phone argument with his girlfriend prompted her to report to his parole officer that he threatened her. Steele denied the claims, but his officer decided the threats amounted to a violation of his 2015 parole. He was taken back to Rikers Island jail in Queens.

“That incident ended up costing me another three years of my life,” Steele told Zenger News. In total, he spent 25 years in jail — but it was the final 3 years, an extra sentence served for a phone call, that hurt the most.

Yet Steele is not alone.

Increasing numbers of lawmakers and prison reform advocates — as well as the formerly incarcerated — say New York’s parole system is keeping people behind bars longer than necessary, overloading ex-convicts with excessive financial and reporting burdens, and giving too much discretionary power to parole officers.

On the other side of the fence is New York’s police unions, who say reforms passed last year — including the elimination of cash bail for misdemeanors and non-violent felonies — are already putting too many offenders back on the street and overburdening police.

Advocates of parole reform, though, say New York’s parole system is woefully poor, and point out that the state reincarcerates more people for technical violations of parole than any other U.S. jurisdiction except Illinois.

Although most U.S. states receive poor marks for their parole policies, New York stands out in having received a “D-” in a 2019 report from the Prison Policy Initiative, a nonprofit that advocates for prison and parole reform.

Moreover, about two-thirds of New Yorkers sent back to prison committed “technical” violations of their parole, according to Alison Wilkey, the director of public policy at the Institute for Justice and Opportunity at New York’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

Wilkey said the net of “technical violations” could be cast very wide by the state’s parole officers, generating a “waste of money and a waste of human potential.”

“New York drastically over-uses incarceration as a punishment for technical parole violations,” Wilkey said.

She said the reasons those on parole might be sent back to prison “include things like missing an appointment with a parole officer, being late for curfew, or testing positive for alcohol – things that would otherwise not be a crime for someone who is not on parole.”

Former prisoners say that the parole system can seem at times like it was designed precisely to make it difficult for them reintegrate and start rebuilding their lives.

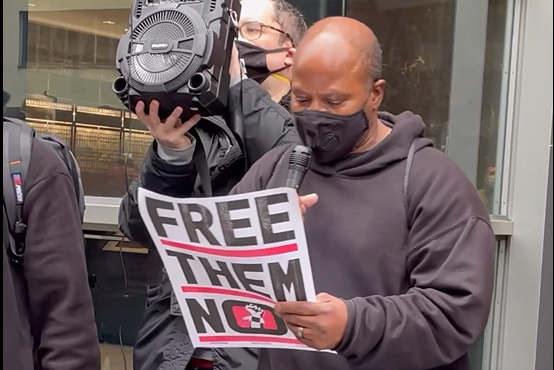

At a recent town hall on parole reform in New York City, Avion Gordon, a member of the nonprofit Katal Center for Equity, Health and Justice, decried arcane parole rules and the discretion given to officers to reincarcerate people for years over benign infractions.

“The parole system, instead of assisting formerly incarcerated people on their journey back into the community, they give people these rigid stipulations that are set in place to make you fail,” Gordon said, pointing in particular to “supervision fees” as an unfair burden.

The fees help cover the costs of parole supervision, including programs like drug treatment. However, parole officers are given wide discretion over the consequences for failure to pay, including reincarceration.

Parole reform advocates say it amounts to an unfair imposition on those who are rebuilding their finances from scratch after years behind bars — and that the consequences leave many unable to escape the system.

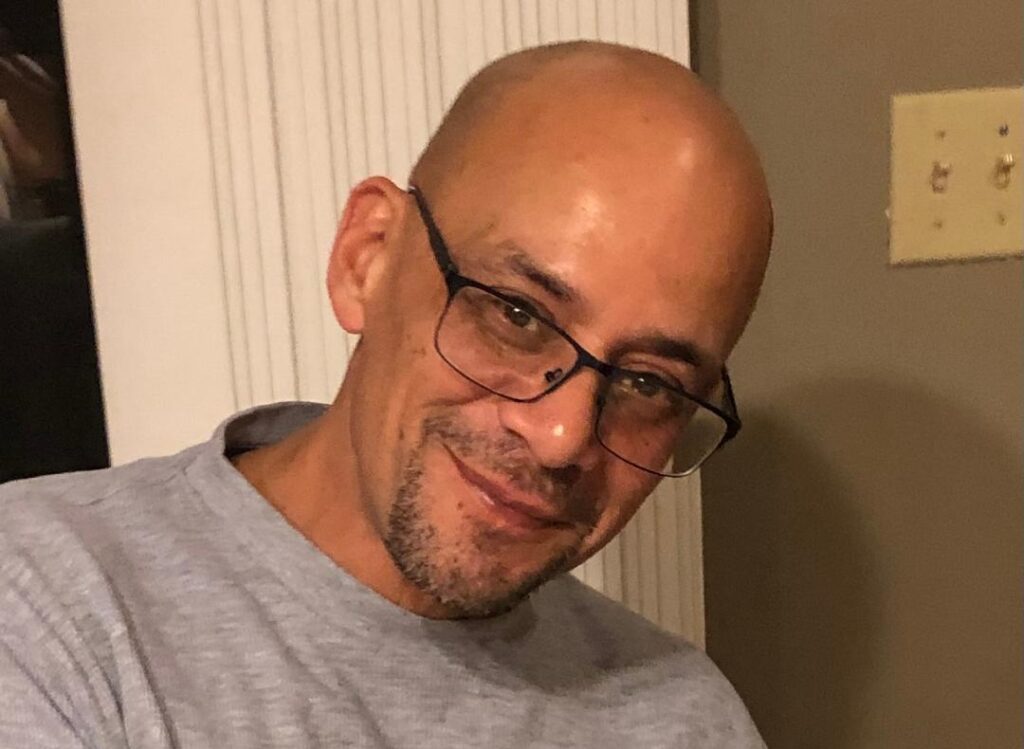

“I have to pay $30 per month, every month, and sometimes it’s a hardship,” says 56-year-old Richard Rivera, who spent most of his adult life behind bars.

Rivera was granted parole in 2019 after serving 39 years in prison over the 1981 killing of a New York police officer in a bar in Queen’s. While locked up, he earned a master’s degree, and now works for a nonprofit in upstate New York helping the homeless and ex-convicts.

Despite doing his best to reintegrate into society as a productive member, Rivera said he still lives in fear of being thrown back in prison for a minor infraction.

“The discretionary power of the parole board and parole officers is great,” he said. “I’m not in control of my life.”

Efforts toward reform have already begun, with pending legislation such as the Less Is More Act currently claiming broad support from lawmakers and district attorneys across the state. Among other things, the bill would give ex-prisoners “earned time credits” for each 30-day block in which they comply with their conditions, instead of just punishing failures to comply. Such provisions are already in place in Missouri and Utah.

So far, the response from police and parole authorities, many of whom are still coming to terms with last year’s bail reforms in New York, has been less than eager.

“Law enforcement is still struggling to get ahold of the consequences of bail reform,” said Wayne Spence, president of the New York State Public Employees Federations, which represents the parole officer’s union.

“Now they want to add to that with ‘Less is More’ parole reform? There are now more parolees on the street than ever before and there are fewer staff to supervise them.”

Spence said he believed the focus of parole reform should instead be to fund better mental health and drug treatment services, which he said would help stem a tide of violent attacks taking place in New York City.

In a statement to Zenger, the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision also denied there were any issues with the comparatively high rate of technical parole violations in the state.

“The issuance of a technical parole violation is not a first resort, but rather a last, as these cases are the result of consistent and escalating violations of an individual’s parole,” said Thomas Mailey, a public information officer at the department.

The corrections department was nonetheless “committed to constantly improving our community supervision processes … so that individuals under community supervision can succeed in reentering their communities and lead a productive life,” Malley said.

To date, 24 U.S. states have passed bills to ban or limit use of incarceration for technical violations and California last year also banned mandatory “supervision fees.”

Wilkey from the Institute for Justice and Opportunity noted that many of the states that have passed reforms in fact lean far more conservative than New York. She said that was due to a federal initiative funded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance to assist 17 states — not including New York — to devise and implement prison reforms to save their state governments money.

She also pointed to a 2019 report from the Columbia Justice Lab and Lippman Commission that said New York spent more than $680 million that year to reincarcerate ex-prisoners for technical parole violations.

“When South Carolina enacted parole reform, the state saved $4.2 million,” Wilkey said, arguing that the savings meant parole reform favored everyone.

“These are funds that could be better spent on reentry, housing, education, healthcare — really anything other than incarceration,” she said. “Mass incarceration is costly and ineffective. … It does not provide accountability for wrongdoing, it doesn’t repair harm for victims, and doesn’t address root causes of illegal behavior.”

Steele, the Bronx native, said he was now back out again and working at a facility on Randall’s Island in New York City while awaiting temporary housing.

He said parole this time was easier to manage than last time, thanks to a more accommodating parole officer — but he said that’s why he still favors reform: to increase transparency and limit individual officer discretion.

“My situation is manageable because now I have a [parole officer] who is more flexible,” he said, adding that the system was too much of a gamble when years in prison can be the result. “My previous PO was very inflexible.”

(Edited by Alex Willemyns and Kristen Butler)

The post New York’s Inflexible Parole System Hindering Second Chances, Advocates Say appeared first on Zenger News.