By Andrew Pantazi | The Tributary – Florida House Republicans and Democrats united against common foes Friday: Gov. Ron DeSantis and his effort to end a Black congressional district in North Florida.

The Florida House congressional redistricting panel voted to send its proposed map to the overall redistricting committee, but not before representatives sparred with conservative redistricting lawyer Robert Popper, who testified at the governor’s request.

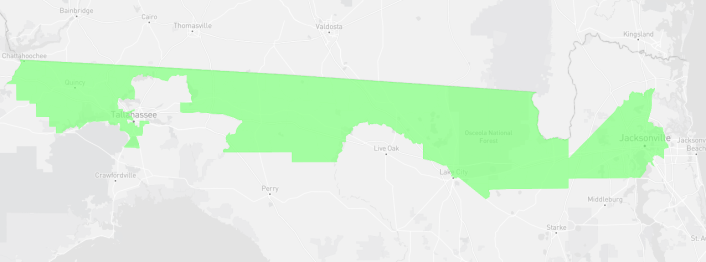

Popper, a senior attorney with Judicial Watch and a former U.S. Department of Justice voting-rights attorney, argued that a congressional district that stretches from Jacksonville to Tallahassee and Gadsden County is “going to have a problem in federal court.”

The hearing presented a rare moment of bipartisan camaraderie, as Republicans and Democrats alike grilled DeSantis’ expert. Still, Democrats requested further changes to how the map treats Black voters in Orlando and demanded the committee publish a secret analysis of racially polarized voting.

Even before the hearing started, House leadership had removed two Republicans from the committee, including Rep. Jason Fischer, a Jacksonville Republican who had said he shared some of the governor’s concerns about the district. The governor proposed an alternative map that would draw two Republican districts in Northeast Florida, instead of one Republican and one Democratic seat.

Fischer said House leaders told him they took him off of the committee because there was a potential he could run for Congress. Fischer is currently running for Duval County property appraiser in 2023. He noted that anyone on the committee could technically run for Congress.

Earlier this month, the Florida Supreme Court unanimously rejected Gov. Ron DeSantis’ request for an advisory opinion on whether Jacksonville’s Congressional District 5 is constitutional, saying the question was too broad and fact-intensive.

On Friday, subcommittee chair Rep. Tyler Sirois and vice-chair Kaylee Tuck pressed Popper on his legal theories, offering a preview into possible future legal fights by DeSantis or those aligned with him.

WHICH LEGAL PROTECTION APPLIES?

Florida’s Fair Districts amendments, approved a decade ago, borrowed language from the federal Voting Rights Act to protect voters from racial and language minorities.

The amendments, in one part, ban districts that deny or abridge racial or language minorities from participating in the political process. That’s nearly a direct quote of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, the Florida Supreme Court ruled.

Another part of the amendments, which the Legislature says protects Black voters in North Florida, bars districts that would “diminish their ability to elect representatives of their choice.” The Supreme Court said that mirrored Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act.

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act previously extended those protections to certain parts of the country based on a formula that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional. However, Florida’s version of Section 5 applied equally to the whole state.

The distinction is important because the case law under Section 2 and Section 5 differ significantly. It’s harder to qualify for Section 2 protections than Section 5 protections.

Map drawers must first be able to draw a compact majority-Black or majority-Hispanic district to qualify for Section 2 protections.

But Section 5’s non-diminishment protections might qualify even if the Legislature can’t draw a majority-Black or majority-Hispanic district, as long as Black or Hispanic voters retain their ability to elect their preferred candidates.

Last decade, courts struck down the Jacksonville-to-Orlando version of the 5th Congressional District as a partisan gerrymander. The courts rejected the argument that the district needed to maintain a Black-majority population when, under Section 5 principles, it could still preserve Black voters’ ability to elect with a lower percentage.

Popper, who said the governor’s office was paying for his flight and hotel, argued the district would fail in court based on federal cases about Section 2’s stricter standards, as opposed to Section 5 cases or last decade’s Florida Supreme Court decisions.

HOW TO MEASURE COMPACTNESS

Popper, along with law professor Daniel Polsby, developed one of the three mathematical scores that the Legislature has used to assess a district’s compactness.

While he said the proposed Jacksonville-to-Tallahassee district wasn’t the worst-scoring district he’s seen, he criticized it as not being compact enough, a complaint raised by DeSantis as well.

“The district is 200 miles long,” he said. “It narrows to three miles wide. It runs through eight counties. It splits four of them.

At one point, he claimed a Supreme Court case indicated Section 5’s non-diminishment protections only apply to majority-Black and majority-Hispanic districts, but the case didn’t say that. In fact, during last decade’s redistricting, the Florida Supreme Court specifically noted that the decision didn’t impact Section 5’s protections.

Sirois pointed that out. “Didn’t the Florida Supreme Court say the exact opposite in its first apportionment decision in 2012?”

Popper said he would need to review his testimony later.

“Can you point us to a district that does not diminish minority voting ability but is more narrowly tailored?” Sirois asked him.

“No, I cannot,” Popper replied, but then he said he believed it would violate the U.S. Constitution.

“Did you explore alternative district configurations and perform the required functional analysis to determine whether a more compact district could have been drawn without diminishing the minority voting ability?” Sirois asked.

“I did not,” Popper replied.

“Are you aware of any court decision holding a state constitutional provision that protects minority voting rights that is insufficient to justify the use of race to draw a district?” asked Rep. Joe Harding, a Williston Republican.

“No,” Popper said. He then cited unrelated federal cases that didn’t deal with the non-diminishment standard.

He claimed it wasn’t clear that one 44 percent Black district in North Florida would allow Black voters to elect their representatives any more than four districts where they made up 10 percent of the voting-age population, even though he admitted he had not analyzed the voting data.

In the current district, even without making up a majority of the population, Black voters make up the vast majority of people who vote in Democratic primaries, and Democrats win the district’s elections.

NECESSARY DELAYS

Sirois acknowledged the House’s congressional redistricting had stalled this month after DeSantis requested the Supreme Court’s intervention, but he said the delay was necessary.

The Florida Senate already approved its congressional map a month ago.

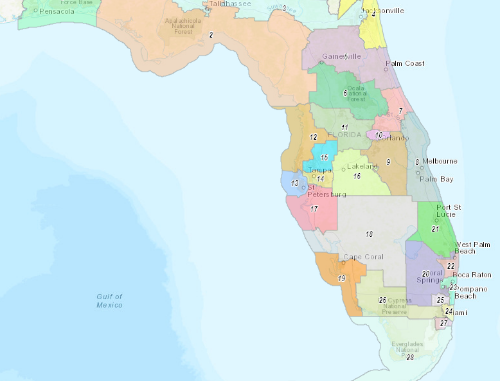

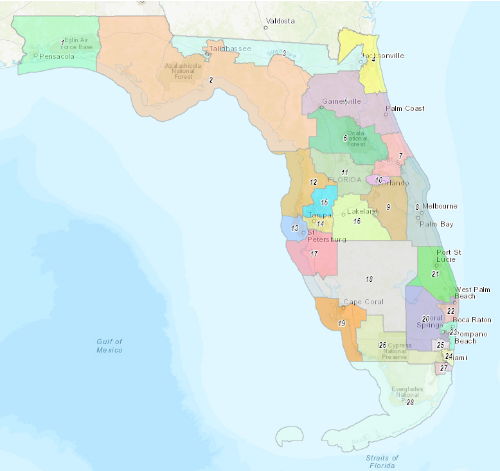

Both the Florida House and the Senate have said the Jacksonville-to-Tallahassee district is a protected Black district, but they differ on whether Orlando Black voters similarly qualify for protections.

The Senate’s map treated an Orlando congressional district as protected to ensure Black voters in Orlando can continue to elect a representative of their choice, but the House staff director, Leda Kelly, said she did not believe that district qualified for the state’s non-diminishment protections.

Black voters would make up 49 percent of Democratic primary voters in the last decade in the Senate version, while the House version would see Black voters make up 39% of the Orlando district’s Democratic primary voters.

Several Democrats noted that staff had submitted an earlier proposal that would’ve been similar to the Senate-approved map, and they asked if the committee could go back to those versions.

Sirois said he and redistricting committee Chair Rep. Tom Leek were open to suggestions for the district.

SECRET ANALYSES

At another point, Rep. Kelly Skidmore, the top Democrat on the committee, asked Sirois about detailed racial-voting analyses performed for the committee’s lawyers. Those analyses haven’t been made public or available to the Democrats on the committee, and Sirois said that’s not likely to change.

After the meeting, Sirois said lawyers hired a consultant to analyze racial voting to prepare for potential litigation.

If that analysis showed that voters from a racial minority don’t vote cohesively, then it might be inappropriate for the Legislature to intentionally draw districts based primarily on voters’ race or ethnicity.

For example, the redistricting staff said one South Florida district crossed the Everglades and was less compact because the district needed to protect Hispanic and Latino voters. But to make race the primary factor for its shape, the committee needs evidence that Hispanic voters must usually vote for the same candidates, and white voters must usually vote for different candidates.

Rep. Tracie Davis, a Jacksonville Democrat, said she wanted the expert who conducted the analysis to testify about any findings.

In North Florida and Orlando, the protection of Black voters can lead to more Democratic seats. Yet, protecting Hispanic voters can lead to more Republican-friendly districts in parts of South Florida.

In its filing to the Florida Supreme Court for a separate state legislative map, the Florida House asked the court to overturn this standard. The House wants the court to say districts protect minority voters even if they don’t vote cohesively. The House legal brief didn’t say share the results of its cohesion analysis.

The House brief argued that the U.S. Supreme Court had never explicitly required cohesion for Section 5 claims. However, past Supreme Court cases did say racial polarization was one of many factors in determining if a minority group could elect their preferred candidates. Lower courts have also required cohesion for Section 5 cases.

Every Republican on the committee voted to send the map to the overall committee.

While Democrats voted against the proposal, they also praised Republicans’ handling of the hearing and expressed optimism about the potential to change the map.

“We were impressed for sure,” Skidmore told the Tributary. “The Republicans definitely were sending a clear message from the House, and it was the right thing to do.”

Skidmore told the Tributary that Democrats would work with Republicans and the staff to try to make changes in Central Florida and South Florida.

The full House redistricting committee will meet this Thursday.

Be the first to comment