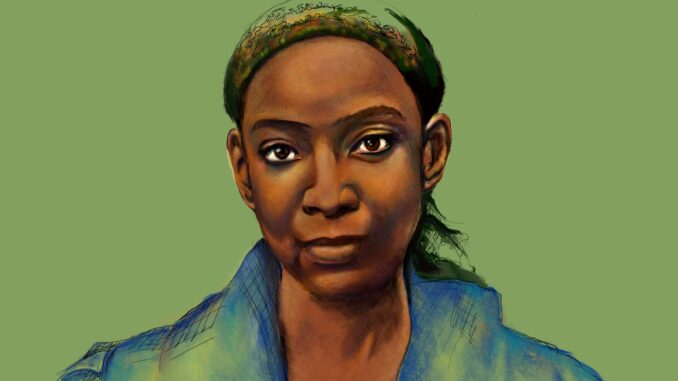

Story by Calvin Baker – When her first novels were published, in the mid-1970s, Gayl Jones’s talent was hailed by writers from James Baldwin to John Updike. Then she disappeared.

In the winter of 1975, a quiet young woman from Lexington, Kentucky, met her Ph.D. adviser in Brown University’s writing program for a series of unsatisfactory tutorials about an ambitious project of hers that had yet to fully reveal itself. The encounters were strange enough that her adviser still recalled them in an interview a quarter century later: “I was doing all the talking, and she would sit rigidly, just bobbing her head in a regal manner. Yet there was a kind of arrogance to her. Perhaps it was the arrogance of an artist fiercely committed to a vision, but I also sensed a bottled-up black rage.” There’s nothing unusual about a young writer seething at the world, especially in the 1970s, when protests and bad attitudes about race, war, and university curricula were so de rigueur that they may as well have been taught at orientation. Likelier than not, his student sensed her (white) adviser’s judgment and withdrew in response—and didn’t think he had much to offer, anyway. While her natural range was virtuosic, his work consisted primarily of a host of popular paperbacks and magazine stories whose titles, including Dormitory Women and “Up the Down Coed,” accurately convey their subjects and sensibilities.

Fortunately, Jones also worked closely at Brown with a true mentor, the noted poet Michael Harper, who’d overseen her master’s degree and would become a lifelong friend. She received her doctorate in 1975 and published her first novel, Corregidora, the same year. The story is told by a 1940s Kentucky blues singer, Ursa, whose troubles with men are refracted through memories of slavery handed down by her matrilineal line:

My great-grandmama told my grandmama the part she lived through that my grandmama didn’t live through and my grandmama told my mama what they both lived through and my mama told me what they all lived through and we were suppose to pass it down like that from generation to generation so we don’t forget.

Or, as the protagonist, whose mother and grandmother were fathered by the same Portuguese slave owner, says at another point: “I am Ursa Corregidora. I have tears for eyes. I was made to touch my past at an early age. I found it on my mother’s tiddies. In her milk.”

Gayl jones was born into a modest family in 1949. Her father, Franklin, worked as a line cook in a restaurant, an occupation she would later give to the father of the narrator of her second novel, Eva’s Man. Her mother, Lucille, was a homemaker and a writer; Jones would incorporate lengthy passages from her work into her experimental fourth novel, Mosquito.

Jones spent childhood weekends visiting her maternal grandmother on a small farm outside Lexington, where she absorbed the stories of the adults around her. It is an unremarkable detail, save for the importance and seriousness Jones later ascribed to this time, as an educated woman channeling those locked out of institutions of so-called higher learning, as a daughter in communion with her mothers, as a formidable theorist validating the integrity and equality of oral modes of storytelling. “The best of my writing comes from having heard rather than having read,” Jones told Michael Harper in an intimate interview conducted the year Corregidora was published. She hastened to add that she wasn’t dismissing the glories of reading, only pointing out that “in the beginning, all of the richness came from people rather than books because in those days you were reading some really unfortunate kinds of books in school.”

Jones published Eva’s Man in 1976, a year after Corregidora. Like Ursa, Eva is a 40ish woman recounting her life story, in this case from prison. Eva landed there after murdering and castrating in graphic fashion a lover she’d spent a few days with—ostensibly because she’d learned he was married. In conversations with a fellow inmate and a prison psychiatrist, Eva “stitch[es] her memories and fantasies into a pattern of sexual and emotional abuse,” as the critic Margo Jefferson wrote. When the psychiatrist asks Eva if she can pinpoint what triggered her to kill the man, she replies only, “It was his whole way.”

Jones called Corregidora a “blues novel,” because it communicated the “simultaneity of good and bad, as feeling, as something felt,” she told Harper. Meanwhile, she considered her second novel a “horror story,” explaining in another interview—with Charles H. Rowell, the editor of Callaloo, an African American literary magazine—that what Eva “does to the man in the book is a ‘horror’ … Eva carries out what Ursa might have done but didn’t.”

The other Black inventors of the modern novel about slavery were Leon Forrest (Two Wings to Veil My Face), who wrote with lyrical, epicurean elegance, and Charles Johnson (Oxherding Tale), whose stories of slave escapes are entwined with the Buddhist quest to get off the wheel of suffering, as well as with the ontological questions of Western philosophy. They bring the high-minded into the lives of the low. By working the other way around, Jones challenges literature itself to embrace other registers of the language, including the obscene, as in this relatively mild example from Corregidora:

A Portuguese seaman turned plantation owner, he took her out of the field when she was still a child and put her to work in his whorehouse while she was a child … I stole [the picture of him] because I said whenever afterward when evil come I wanted something to point to and say, “That’s what evil look like.” You know what I mean? Yeah, he did more fucking than the other mens did.

Jones elaborated on the politics of the English language with Harper:

I usually trust writers who I feel I can hear. A lot of European and Euro-American writers—because of the way their traditions work—have lost the ability to hear. Now Joyce could hear and Chaucer could hear. A lot of Southern American writers can hear … Joyce had to hear because of the whole historical-linguistic situation in Ireland … Finnegan’s Wake is an oral book. You can’t sight-read Finnegan’s Wake with any kind of truth. And they say only a Dubliner can really understand the book, can really “hear” it. Of course, black writers—it goes without saying why we’ve always had to hear.

Telling stories out loud was a matter of survival and wholeness for a community forbidden to read, as well as an act of rebellion, and the way Jones wields this tradition transforms even a kind of nursery rhyme shared between daughter and mother into something dirty, dangerous, and important.

I am the daughter of the daughter of the daughter of Ursa of currents, steel wool and electric wire for hair.

While mama be sleeping, the ole man he crawl into bed …

Don’t come here to my house, don’t come here to my house I said …

Fore you get any this booty, you gon have to lay down dead.

When Harper asked for her thoughts on the architects of 20th-century Black literature, namely “Gaines, Toomer, Ellison, Hurston, Walker, Forrest, Wright, Hughes, Brown, Hayden et. al,” Jones pointed out the wide variation in a group that to the mainstream might appear homogeneous:

You know, I say the names over in my mind, and I think about those people who will speak of black writing as a “limited category,” the implication being that it’s something you have to transcend. And it surprised me because I thought critics had outgrown that sort of posture.

She certainly had. Whereas Baldwin famously lashed out at the protest-novel straitjacket put on mid-20th-century Black writers—“The ‘protest’ novel, so far from being disturbing, is an accepted and comforting aspect of the American scene”—Jones came of age breathing the air of the Black Arts Movement. Founded by LeRoi Jones (no relation), who combined immense talent, critical acumen, and, after being brutalized by the police, a rusty shank of disdain for the lassitude of white America, the movement advanced the idea that white people’s approval was beside the point. Why bother being the Black exception in a country where attempts to control the mind and body of Black people knew no bounds? In his fiery 1965 manifesto, “The Revolutionary Theatre,” LeRoi Jones described the mission for Black artists this way: “White men will cower before this theatre because it hates them … The Revolutionary Theatre must hate them for hating.” Gayl Jones’s “fuck off ” was less explicit but no less radical: She wrote fiction as if white people weren’t watching.

Be the first to comment