PHOENIX — A jury in Phoenix found that a sheriff’s deputy was justified when he shot a Hispanic man in the back as he surrendered with only his rosary in his hands, a verdict that comes after months of both peaceful protests and fiery riots nationwide centered on questionable police shootings of black people.

Jurors also deadlocked on a federal civil rights claim that the shooting violated the man’s Fourth Amendment protections.

The outcome shows the weight of the law remains stronger than the power and momentum of the justice reform movement. But it also shows how far the movement has shifted the national conversation, legal scholars said.

The family’s attorney vowed to appeal.

The jury of four men and four women found that Pinal County Sgt. Heath Rankin was not liable under state wrongful death statutes because he was justified in shooting 43-year-old Manuel Longoria twice.

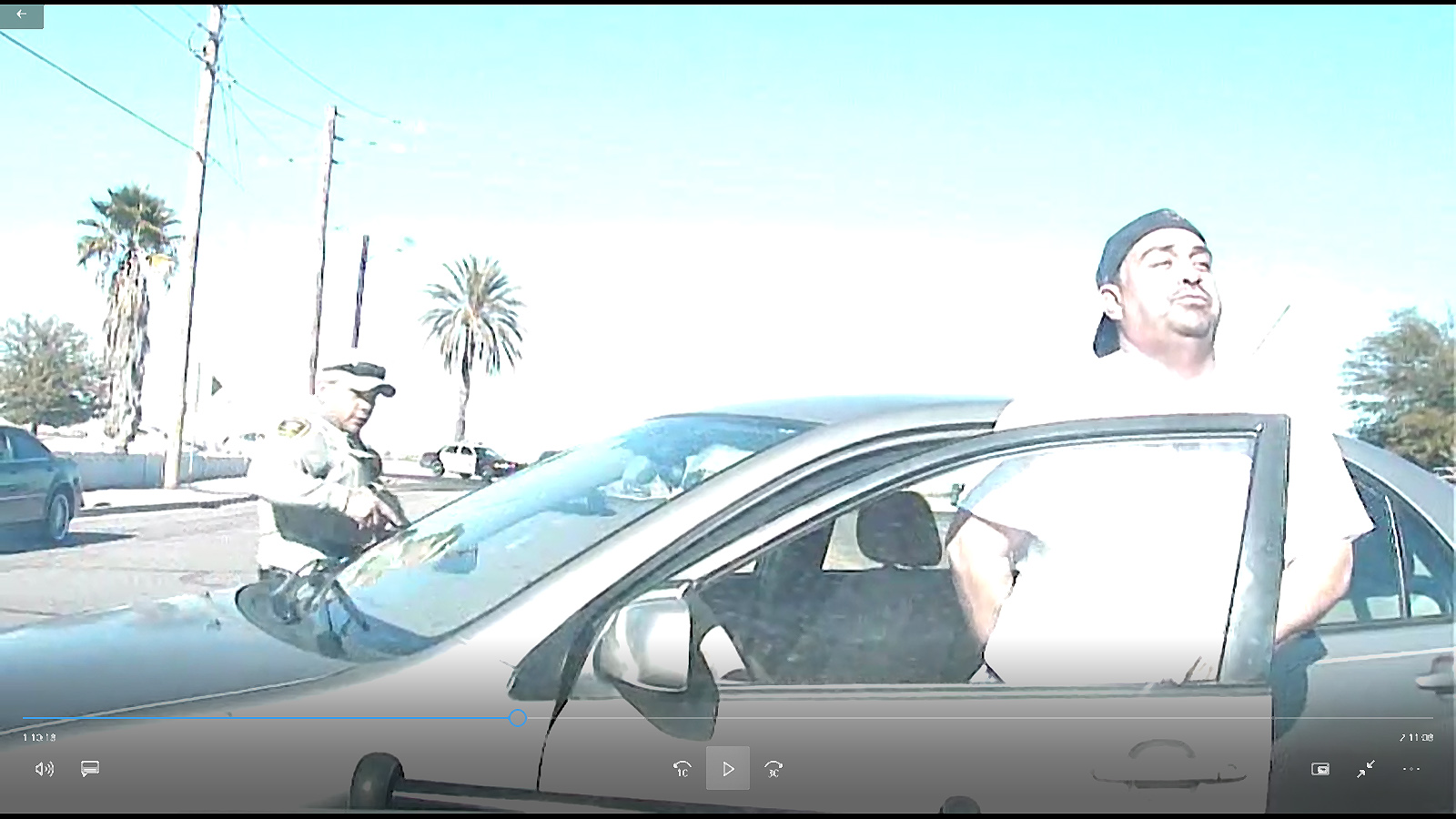

The 2014 incident, which began as a 70-minute police car chase and ended with a standoff, was caught on multiple police and bystander videos. Police responded to reports of a stolen car, and pursued Longoria as he circled around town to reach his wife’s house.

Throughout the chase, Longoria said he wanted to die, that he had a gun and would not surrender. The chase ended when police clipped his car. Longoria got out, kept his right hand concealed and did not initially give up, even after being struck by bean-bag rounds.

Longoria’s children filed a federal excessive force claim and a state wrongful death action in the U.S. District Court in Phoenix.

At trial, attorneys painted two contrasting accounts of what happened on Jan. 14, 2014 in Eloy, Arizona, a farm town halfway between Phoenix and Tucson.

Throughout the trial, it was impossible to ignore the racial undertones and the wider political climate underpinning the case. The powerful and powerless shared Courtroom 604 in the Sandra Day O’Connor United States Courthouse.

The Longorias are a big blue-collar family. Most are Latino, like most of the population in Eloy. They testified about their struggles with crime, delinquency, drugs and long hours as tow-truck operators or bleach factory workers. Manuel Longoria couldn’t read a plea bargain when he signed it, his wife testified.

Opposite the family sat Rankin, who is white, with his all-white defense team, the white judge, the white journalist and the mostly white jury.

Lawyers for the family told the jury that police had a plan to arrest Longoria, who was wanted on a warrant for violating parole, and that it was working until Rankin arrived. They depicted Rankin as a man who made his mind up to end the conflict himself and who disregarded orders and protocol to rush to the scene. Plaintiffs’ lawyers argued Rankin’s actions were rash and unreasonable.

No officer ever saw Longoria with a gun, and no gun was never found.

But Rankin’s attorneys shifted the blame to Longoria, a man they said was hell-bent on “suicide by cop.” They described his actions as reckless and dangerous to the public, police and members of his family. Lawyers said Longoria was fleeing an arrest warrant, driving a stolen car, high on cocaine and acting like he had a gun.

Defense lawyers argued Rankin acted reasonably, based on everything he understood at the time of the shooting — that Rankin had to act because the lives of police and the public were in imminent danger, and Longoria’s actions caused his own death.

Last week’s verdict came after three days of deliberation following a nine-day trial.

Throughout the case, Rankin sat stoically in his crisp, tan Pinal County Sheriff’s Office uniform, speaking calmly and professionally on the stand.

Longoria’s son, Christian Longoria, sat in court every day wearing a dark shirt and tie, often with his head bowed and in his hands. Testifying, he appeared confident and personable, often smiling at the jury and joking about fond memories of his dead father.

Rankin, his defense attorney, Kathy Wieneke, and the Pinal County Sheriff’s Office all declined to comment for this story. PCSO cited the prospect of ongoing litigation.

Christian Longoria also declined to speak.

Manuel Longoria’s father-in-law, Dewayne Powell, called the verdict “bullshit.”

“We thought we’d won. We’re mad. We want to know why,” Powell said. “Judges are always going to go to the cops’ side. The courts are stacked toward the cops.”

Attorney Jesse Showalter, who represented Manuel Longoria’s seven children, said the verdict was “disappointing,” but that the family would seek a renewed claim.

“The fact that the jury was deadlocked on the federal charge reflects how divided this country is,” Showalter said.

The case cast a spotlight on deep societal divisions between communities of color and police, and between the powerful and powerless. Rankin is white; Longoria was Latino.

It also raised questions about how far the law goes in protecting law enforcement officers and whether those protections appropriately protect honest cops who make difficult split-second life-or-death decisions, or if it renders bad cops untouchable.

As Wieneke told jurors repeatedly, the law says an officer doesn’t have to be right, only reasonable.

Under the legal principle of qualified immunity, law enforcement officers are rarely punished, legal analysts familiar with the Longoria case said. Police cannot be held liable unless a jury rules the officer violated the Fourth Amendment. To prove that, plaintiffs must show the officer’s actions were not “objectively reasonable.”

The verdict hinged on whether the jury believed Rankin on the stand and whether panelists thought he acted reasonably or recklessly, based on his training and the “totality of the circumstances” known to him at the moment he fired his AR-15 rifle.

The jury had to untangle multiple discrepancies between Rankin’s testimony at trial and his earlier statements. He also contradicted the testimony of other officers, as well as video evidence.

Rankin’s account differs from what he told investigators during his debrief hours after the shooting.

Jurors struggled with the testimony. During deliberations, they asked to see Rankin’s earlier statements and had some of his courtroom testimony read back, according to Longoria’s widow, Lynnette Longoria, and others familiar with the developments.

The plaintiff’s attorney, Showalter, began his case telling the jury there were two stories — one of successful police action, and another after Rankin arrived.

He began the final argument: “Hand’s up, don’t shoot,” an ode to the chants popularized in protests of the Ferguson, Missouri, police shooting of Michael Brown seven months after Longoria’s.

Defense lawyer Wieneke’s summation began with a different quote. For 24 seconds she yelled police commands: “Show me your hands! Get on the ground!” She made the point that’s how long Longoria had to surrender and end the ordeal safely.

“Mr. Longoria was on a mission — a mission to die at the hands of police,” she said as she began her defense.

In addition to Rankin’s credibility, the case hinged on the evidence Judge Susan Bolton allowed or denied.

Bolton dismissed the case in 2016, before that decision was reversed on appeal. At trial, she repeatedly sided with Rankin’s team on key motions. Overall, Bolton ruled in routine objections twice as often in Rankin’s favor as against.

The jury never saw the full video with sound shot by a bystander from about 200 feet away. Wieneke’s team argued that because sound travels slower than light, it could not be relied on as accurate.

Rankin testified that the video, taken from across the street, “was a completely different perception of what happened.”

Other officers testified it wasn’t reality, partly because it didn’t capture their emotions during the tense standoff.

With sound, the video clearly shows Longoria turn his back, thrust his hands in the air moments before two loud booms. The booms, from the AR-15, contrast the crack-crack sound of bean bag rounds being fired into Longoria.

Based on the weather at the time of the shooting, the time lag is 0.175 seconds.

Longoria’s jerking motion that Rankin said he thought was a shooter’s stance occurred at least 2.5 seconds before he fired.

The jury never heard that, however. Nor did they see the autopsy, which the judge ruled inadmissible.

The autopsy, obtained through a public records request, concluded that two fatal bullets struck Longoria in the back below his shoulder blade, about an inch apart.

On the stand, Rankin was adamant. Asked if he shot Longoria in the back, he testified firmly: “No.”

Jurors also did not see his or some other police statements taken in the hours after the shooting that contradict other details of Rankin’s account.

A forensic report from a police practice expert was not admitted into evidence. It concluded that the shooting was not reasonable, in part because no other officers fired. At trial, Wieneke attacked the expert’s credibility pointing out that he couldn’t name any of those officers, and he hadn’t trained police since the early 1990s.

Powell, Longoria’s father-in-law, was angered by the omissions.

“If they don’t let the jurors hear the sound, they don’t know nothing,” he said, convinced it would have changed the outcome.

The Longoria shooting trial came after months of both peaceful protests and fiery riots nationwide centered on questionable police shootings of black people.

The outcome shows the weight of the law remains stronger than the power and momentum of the justice reform movement. But it also shows how far the movement has shifted the national conversation, legal scholars said.

“The deadlock is a symptom of the moment,” said Ben McJunkin, the associate deputy director of the Academy for Justice at Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O’Connor Law School, who reviewed key evidence and arguments in the Longoria case before trial.

He was surprised by the impasse, but not by the finding that Rankin wasn’t at fault for the death. That’s because the legal standards “are incredibly high and make it very unlikely civil suits can be successful,” he said.

He pointed to research that shows many plaintiffs’ attorneys often screen out cases involving a qualified immunity defense. They won’t even take them.

When they do, they often settle out of court. Of those cases that don’t, two-thirds get dismissed, he said.

While 20% of dismissed cases get reversed on appeal, the same is true for only 8% of cases involving qualified immunity, according to research cited by McJunkin.

Juries side with the defense two-thirds of the time, which goes up to 88% of the time when qualified immunity is in play.

The Longoria trial is a rarity.

“I don’t think we would have gotten this verdict before George Floyd,” McJunkin said.

After the shooting, the Longorias painted the backs of their cars and trucks with: “Fuck the PCSO. NWA said it best.”

Wieneke tried to get them to acknowledge the words came from the gangster rap group popular in the 1990s whom police blame for a rise in lyrics espousing violence to officers.

On the first day of the trial, a small protest gathered in front of the county prosecutor’s office, just a few blocks away. Protestors demanded justice for Ryan Whittaker, shot twice in the back by Phoenix police in May.

In closing, Showalter played to those tensions.

“The Longorias, all of them, did an incredibly brave thing. They stood up to a government actor and said this was wrong,” he said. “It’s hard to tell police they’re wrong.”

Incidents like the one in 2014 “happen in American all too much,” he said.

“The Bill of Rights protects us from the government,” Showalter said. “The system has to apply to everybody, or it will apply to nobody.”

In response, Wieneke said, “No officer wants to shoot somebody. We cannot ask them to do the impossible. We cannot ask them to be robots. The law does not and cannot require them to be perfect.”

McJunkin said the verdict will be seen by police as a reaffirmation of that view and for Black Lives Matter supporters, it will send a dispiriting message.

To the Longorias it sends another message: defiance.

Powell said the message on his truck will stay there for the rest of his life, even though his son was once a PCSO deputy.

“We tried the silent protest way. We don’t want to start a riot. Maybe that’s what we should’ve done,” he said.

For the rest of my life, I will never trust a cop,” he said, noting he never thought that until the shooting. “I’ll raise my grandkids not to trust cops.”

Lynnette Longoria said she was not surprised at the outcome. But she’s also undeterred.

“I’m not discouraged,” she said. “I have the rest of my life to do this. I’ll keep fighting.”

(Edited by Matt Rasnic and Natalie Gross)

The post Jury: Arizona Deputy Not at Fault for Fatal Shooting of Unarmed Man appeared first on Zenger News.