Interruptions to the supply chain from the COVID-19 pandemic have limited supplies of essential gear for doctors and nurses, but some entrepreneurs and makers and turned to new technologies to fill the gap.

Shortages this spring exacerbated existing shortages of personal protective equipment for frontline healthcare providers, and ventilators for the infected, worldwide.

At one point, more than 30% of U.S. healthcare workers had two weeks of N95 face masks, considered the standard for protection, remaining, and 22% had none at all, according to GetUsPPE.org, a grassroots organization working to source personal protective equipment for U.S. healthcare providers. The organization also found only 22% had two weeks of face shields, and 36% had already run out.

Dr. James Lawler, an infectious disease specialist and public health expert at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, projected if 96 million Americans will contract the virus, 1.9 million of those will need a stay in a hospital intensive care unit, and a million of those will need a ventilator. As of June 3, more than 1.8 million Americans had contracted the virus, according to figures compiled by Johns Hopkins University.

However, an April report from the Center for Health Security at Johns Hopkins estimated the country only has 170,000 ventilators, and even that is an optimistic guess as no centralized records are kept of the number.

“The need for ventilation services during a severe pandemic could quickly overwhelm these day-to-day operational capabilities,” the John Hopkins report says.

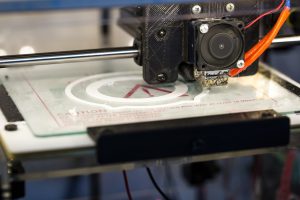

To supplement the shortage, private citizens and non-medical businesses and organizations are adapting their own manufacturing processes, such as 3D printing—also known as additive manufacturing—to meet demand. New York-based design company Tangible Creative produced 25,000 PPE units by mid-April using their banks of 3D printers and even schools are contributing.

Dell Technologies has reported on various staff members who are using their personal 3D printers to manufacture PPE. Simon Seagrave, director of the Dell Technologies demo team, prints eight face masks a day from his Massachusetts home using an open-source design published by the National Institutes of Health.

Maxwell Andrews, a Dell technology strategist in San Francisco, joined Helpful Engineering, a volunteer global group of engineers, scientists and doctors helping fight the pandemic. He designed an origami face shield that can be cut from plastic with a personal laser cutter and then folded flat for easy transport and storage.

Elsewhere, the European Association for Additive Manufacturing launched a call to action to the non-medical 3D-printing sector to help in the printing of valves, masks and other crucial medical material in the fight against COVID-19. According to the association, the response has been encouraging, although it has not released any hard data on it.

This rally of aid hasn’t been without controversy, however. UK-based InterSurgical drew criticism for not allowing hospitals in Italy to 3D print patented respirator valves during the epidemic. The company subsequently allowed its designs to be used, once the scale of the crisis was brought to light.

Filip Geerts, director general of the European association, says such issues can be mitigated, as long as regulators openly communicate with manufacturers, large and small, about hospitals’ specific needs; ease patent and Customs restrictions; and facilitate provision of printing plans.

“I believe that the additive manufacturing sector can play an important role in sustaining the effort of hospital workers in the middle of this emergency. However, it is in the best interest of all to clarify the regulatory issues in order to move forward quickly and in a way that is not going to delay immediate actions.”

However, the scale of the shortages mean that additive manufacturing is at best a stopgap measure. “3D printing is good for bespoke production, things that are only used for a specific purpose,” said Charles Bellm, managing director of InterSurgical. “Injection molding is more useful for the mass production we need now. 3D printing is a slow process, which isn’t suited to this situation.”

Regardless, healthcare organizations coping with shortages are taking whatever assistance they can get until large scale quantities become available.

However, Nevaris A.C., CEO of Tangible Creative, was critical of the U.S. government response, saying the situation in the U.S. shouldn’t have reached this point. “This has been handled so poorly,” he said, and crowdsourcing and grassroots organizations are having to fill the gap for federal assistance.

(Editing by Tom Pleasant and Allison Elyse Gualtieri)

The post Health care equipment shortages lead to innovation, conflict appeared first on Zenger News.