NEW DELHI — Dozens of bloated and decomposing bodies, washing up on the banks of Indian rivers such as the Ganga and Yamuna, have raised fears of the Covid-19 crisis spiraling out of control and contaminating water bodies.

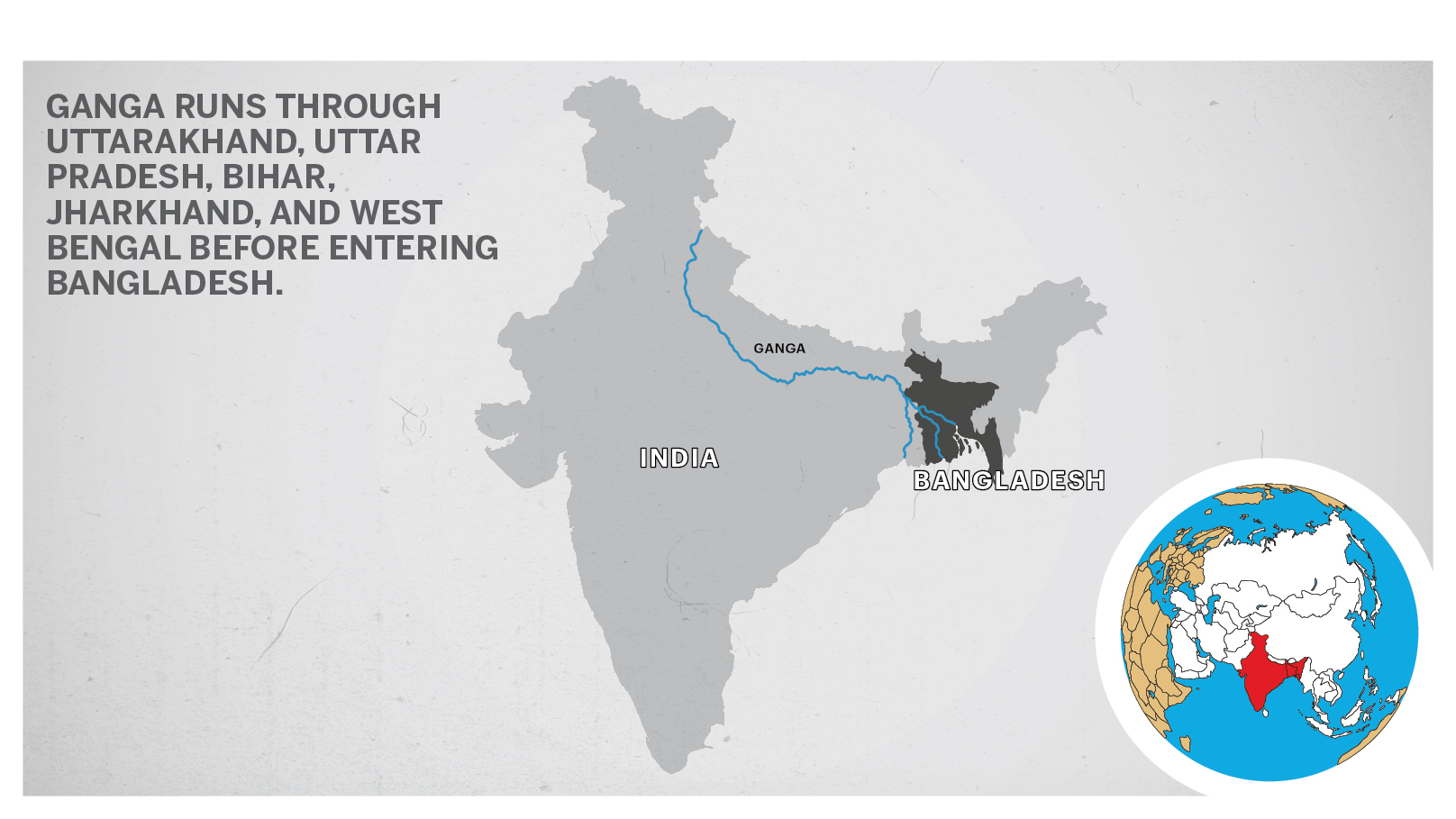

At least 70 bodies were fished out of the Ganga at Chausa, a village in the eastern state of Bihar’s Buxar city, which borders the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, as per official figures. The Ganga is a lifeline to millions of Indians who live along its course and depend on it for their daily needs.

Aman Samir, district magistrate, Buxar, said the administration launched an investigation to determine the origin of the bodies.

“It was revealed that the bodies were three to four days old,” Samir said. “So, it is clear that the dead do not belong to Buxar district.”

He said the district magistrates of the bordering towns held talks to take stock of the situation. The district authorities collected samples from the corpses for Covid-19 tests and DNA sequencing. The process of disposing of these bodies was underway.

“All night, the bodies were taken out, and we conducted post mortems. Since the bodies were decomposed, the cause of death is yet to be established,” the Buxar administration said in a press statement.

“We have saved DNA traces to help identify the corpses.”

Samir said a strict vigil was ordered, and boat patrols will be conducted to prevent a repeat of such an incident.

“The incident of corpses floating in Ganga in Buxar region of Bihar is unfortunate,” tweeted India’s Union Minister of Jal Shakti Gajendra Singh Shekhawat.

“This is definitely a matter of investigation. The Modi government is committed to the cleanliness of ‘mother’ Ganga. This incident is unexpected. The concerned states should take immediate cognizance.”

Bodies floating up, nothing new in India

It is illegal to immerse corpses in the Ganga and other rivers, but bodies show up frequently. Saints, children, and those from low-income families are sometimes immersed in these rivers.

Previously, in 2016, about 80 corpses — mostly half-burnt or decomposed — surfaced on the Ganga river in Uttar Pradesh. The National Green Tribunal, India’s environment court, had criticized the government for its failure to control river pollution and asked the water resources and environment ministries to explain.

More than 100 bodies, in a similar state of decay, were found floating in the Ganga in January 2015 and got stuck on the banks and sandy islands at the Pariyar ghat in the Safipur area of Unnao, an industrial city in Uttar Pradesh.

During the Spanish Flu in 1918, India witnessed similar scenes of bodies floating up the river Narmada. That pandemic had killed around 13.88 million people in India.

The latest incident has sent ripples across the nation as many believe the dead are Covid-19 victims. Though official figures state the number of bodies at around 70, eyewitnesses claim the numbers could be more.

“We are in fear,” Ashwani Kumar Verma, a resident of Chausa, told Zenger News. “Some people can’t afford cremation expenses. There is also a shortage of wood to burn the dead.”

“About 40-50 bodies of Covid-19 victims are being pushed into the Ganga every day. It is condemnable. A magistrate must be deployed to ensure proper funerals.”

Politics has also begun over the issue. Pappu Yadav, Bihar’s opposition politician, tweeted about “more than 500 corpses floating in a river” and criticized the state’s Chief Minister Nitish Kumar. No other reports were indicating this claim.

A day after the Buxar incident, reports of bodies floating down the river came from Ghazipur in Uttar Pradesh, a town about 50 kilometers (31 miles) upstream from Buxar. There were also reports of bodies floating in the river Yamuna in Uttar Pradesh’s Hamirpur a day ago.

India is witnessing unabated Covid-19 deaths, and images of people scrambling for funerals and burials have flooded the world media. More than 250,000 people have died so far in the pandemic that began more than a year ago.

Crematoriums and burial grounds are running out of space. Funeral pyres are being lit in car parking lots and along pavements. The sudden surge in cremations has also seen wood — an essential element in Hindu cremations — supplies dwindling.

Burdening the overburdened environment

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi wanted to bring back the Ganga, a river of cultural legacy, to life through a ‘National Mission for Clean Ganga’. But locals are raising alarm that river contamination could be catastrophic.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have said there is no evidence that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, can spread to people through oceans, rivers, or swimming pools.

But what India is experiencing has no precedence.

“Corpses presumably of Covid-19 victims floating in Yamuna and Ganga is a shame,” Manoj Misra, Delhi-based environmentalist and clean river campaigner, told Zenger News.

“If true, then rural India, marked by poor or absent healthcare infrastructure, is affected. Unless urgent ameliorative steps are taken, it could result in mayhem.”

Misra said it was a cause for worry if the river water and life in it are found to be infected with the virus.

“Whether a corpse can be a source of infection is poorly researched, and, hence, the precautionary principle must be applied here, and river waters tested at priority,” said Misra

The attention of health authorities, ministers, citizens, and national and international media has been on the Covid calamity in significant cities.

It’s estimated that around 70 percent of surface water in India is already unfit for consumption. Almost 40 million liters of wastewater enter rivers and other water bodies every day, with only a tiny fraction adequately treated.

“Release of pollution upstream lowers economic growth in downstream areas, reducing the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth in these regions by up to a third,” notes a study by the World Bank. “To make it worse, in middle-income countries such as India, where water pollution is a bigger problem, the impact increases to a loss of almost half of the GDP growth.”

Ailing rural healthcare infrastructure

There are more than 600,000 villages in India where primary healthcare facilities are lacking. Further, access to medical oxygen, ventilators, intensive care units, and life-saving drugs sold at exorbitant prices in the black market make the problems multifarious.

“Most people in rural India are still unaware of the symptoms of the virus,” Kamini Kumar, an Allahabad-based ophthalmologist, told Zenger News.

“My gardener contracted the virus recently, but he thought it was viral fever. I told him to get himself vaccinated for Covid-19 [as the symptoms matched] after 45 days, but he didn’t understand the context. He was clueless.”

Doctors and medical professionals believe that there is not enough medical capacity to take care of a sudden spike in rural areas considering the rate at which the Covid-19 pandemic is spreading.

“Urban India is already facing a lot of bed shortage,” Aditya Jayaraman, a New Delhi-based consultant in internal medicine, told Zenger News. “In the case of rural India, the number of villages, districts is quite high.”

“The problem with this second wave is if one gets affected, then all the family members are getting affected. The sudden exponential surge is the problem. If the curve were a little more gradual, we would have fought the virus.”

However, Jayaraman thinks that the dead bodies in the rivers will not spread the virus since it is spread mainly through droplets in the air.

“But definitely, decomposing bodies in water can lead to bacterial infection and other problems, which can make people fall sick. If these people visit the hospitals, then there is a high possibility of them catching the virus there.”

(Additional reporting provided by Pallavi Mehra.)

(Edited by Gaurab Dasgupta and Vaibhav Vishwanath Pawar. Map by Urvashi Makwana.)

The post Mass Dumping Of Suspected Covid Dead In Indian Rivers Raises Alarm appeared first on Zenger News.