He didn’t have a flushing toilet as a child and, when he finally moved into a house that had one, he was fascinated and continually flushed it – annoying his grandfather, who paid the water bill.

As a U. S. Supreme Court justice, his tastes are remarkably modest. His ideal vacation is driving cross-country in a 40-foot motor home, often staying in Walmart parking lots.

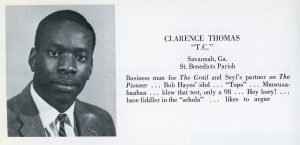

Clarence Thomas, the famously silent jurist, tells his own life story in a new documentary, “Created Equal: Clarence Thomas in His Own Words” which makes its national television debut May 18 on PBS.

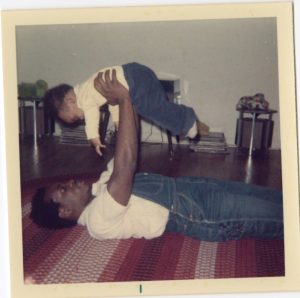

The two-hour film explores Thomas’ life, from his 1948 birth in the small town of Pin Point, Georgia, to his upbringing as a poor black kid in the segregated South, to his liberal phase in college, to his conversion to conservatism, to his rise to the nation’s highest court.

“I don’t expect that [Thomas] will convince you on the issues,” Pack said. “But I think it’s impossible to watch this film and not see that he’s a serious, thoughtful person—whose ideas are worth considering—with a very powerful and inspiring life story.”

After the retirement of Thurgood Marshall, the first black Supreme Court justice, Thomas was appointed to take his seat. His confirmation seemed assured until a former colleague from two of his prior executive branch jobs, Anita Hill, came forward with sexual harassment allegations, prompting an investigation from the Senate Judiciary Committee, chaired by then-Sen. Joseph Biden. Opinion polls at the time showed a small majority of the public believed Thomas should be confirmed, which he was 52-48 in 1991; Biden, the likely Democratic nominee for president, is facing his own uncorroborated sexual allegations.

“Created Equal” gives the public a fuller picture of one of the nation’s most intriguing public figures, said Michael Pack, who directed the film and produced it with Gina Pack, his wife.

Michael Pack, filmmaker with a long history of producing public television and serving in Republican administrations, is from Maryland.

Thomas rarely speaks publicly—even during high court oral arguments. He told some of his personal story in a 2007 book, “My Grandfather’s Son.” Thomas wanted to go beyond the book, Pack said.

“He wanted something in the film and television world,” said Pack. “Not so much that he wanted it; his friends felt more strongly about this than Justice Thomas. …People were encouraging him to get the truth out there. He was a little reluctant, to be totally honest.”

Thomas approached Pack through mutual friends, Pack said.

It was not a random choice for Thomas and his wife, Virginia, to work with Pack. As president of Manifold Productions, Pack has produced a number of documentaries on conservative themes.

Pack served as senior vice president of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which oversees PBS, from 2003 to 2006. He also served as president and CEO of the Claremont Institute, a conservative think tank. In 2018, Trump nominated Pack as CEO of the U.S. Agency for Global Media, which oversees Voice of America. Democratic senators raised questions about Pack’s film work with Steve Bannon, former adviser to President Trump.

A veteran of public broadcasting, Pack testified in front of a Senate committee last year. His nomination was scheduled for a committee vote this week, which was postponed.

Very little of the documentary covers Thomas’ Supreme Court career. Most of it is devoted to his childhood in the segregated South. More than three years in the making, the film draws from more than 30 hours of interviews with Thomas and his wife.

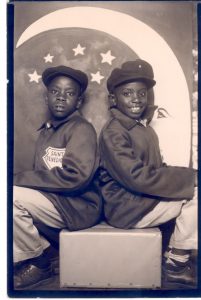

Thomas credits much of outlook on life to his hard-working, God-fearing grandfather who raised him and his younger brother after his single mother could not afford to care for them. “My grandfather understood that education was the key because he didn’t have it,” Thomas says in the film.

His initial reaction to the racism he experienced growing up in Georgia was to try to be perfect. But when he got to the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, he started speaking out against racism, joining protest rallies and other activities in support of black activists, including the Black Panthers.

His relationship with his grandfather became “horrible,” Thomas said. After a violent protest disrupted campus, Thomas had second thoughts. He prayed, asking God to take the anger out of his heart. “That was the beginning,” he said, “of the slow return to where I started.”

When Thomas graduated from Yale Law School in 1974, unlike his classmates, he had trouble finding a job. He attributed that to potential employers assuming affirmative action was behind his acceptance to the prestigious law school.

Thomas eventually got a job offer from John Danforth, Missouri’s attorney general. Danforth was a Republican and Thomas initially felt that working for a Republican was “repulsive.” Nevertheless, he took the job. His experience there began to change his mind. He previously believed that much prosecution of African Americans was politically motivated. In the Missouri courts, he met black crime victims who led him to reconsider his views.

Next, Thomas worked for Monsanto and became disenchanted with what he perceived as half-hearted efforts by the agriculture company’s equal employment executives to advance black employees.

Thomas’ journey to conservatism was well underway when in 1979 he went back to work for Danforth, by then was a U.S. senator. Thomas was appointed by President Ronald Reagan to be chairman of the Equal Opportunity Employment Commission and a federal judge before his Supreme Court nomination.

The film’s title reflects Thomas’ belief the courts should adhere strictly to the original intent of the founding fathers, who wrote “All men are created equal” at the start of the Declaration of Independence.

The film has gotten mixed reviews. A common criticism is that the documentary is one-sided. Pack acknowledges this criticism, but said it was a conscious artistic choice.

“Our documentary doesn’t pretend to be objective,” Pack said. “We were true to what we said we would deliver, which was a very important person’s view of the world. … It’s worth hearing.”

Including “in his own words” in the film’s title alerts viewers to the fact that it is not a balanced documentary, he said. His film is no different from many other documentaries that allow public figures to tell their own stories, Pack said.

One thing Pack did not allow was Thomas’ interference in the production of the documentary. The Supreme Court justice gave him “editorial independence” and a “high degree of trust,” Pack said.

Asked in a recent interview what Thomas’ reaction is to the film, Pack said: “He has yet to see it.”

“Created Equal: Clarence Thomas in His Own Words” will air on PBS stations around the country on Monday, May 18.

(Edited by Richard Miniter and Allison Elyse Gualtieri)

The post For the first time, Clarence Thomas tells his story on television appeared first on Zenger News.