Chinese intelligence agencies appear to have repeatedly penetrated their U.S. counterparts in the past 20 years, and the spying has led to federal prosecutions and lengthy prison terms for American who were involved.

Officials from the Justice and State departments and the FBI have warned with increasing alarm about China’s espionage capabilities—more recently focusing on its use of researchers and academics to steal proprietary technologies and other information. Espionage and counterintelligence have been staples of statecraft for centuries. While China hasn’t turned away from traditional spycraft, it increasingly relies on scientists and other nontraditional spies, to sweep up secrets.

A handful of federal prosecutions involving U.S. intelligence employees in the past two decades shed light on Beijing’s capabilities, said former intelligence officials, who consider China to be on par with Russia as the America’s top espionage threat.

“What I’ve seen, in terms of the methods that they’re employing, it’s really no different than the things we’ve seen out of the Russians,” said Tracy Walder, a former CIA officer and FBI special agent.

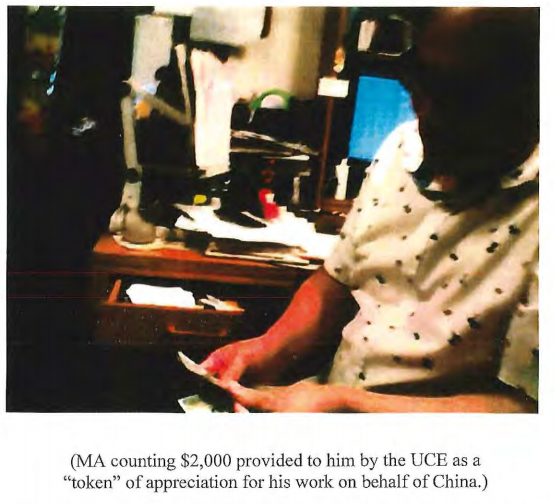

The most recent high-profile case involved Alexander Yuk Ching Ma, a former CIA officer and contract linguist for the FBI. Ma was arrested in August, nearly 20 years after he and a relative, also a former CIA officer, allegedly met with five Chinese intelligence officials over a three-day period in a Hong Kong hotel room, according to an FBI affidavit.

Ma and his unnamed relative, who has not been arrested because the relative “suffers from an advanced and debilitating cognitive disease,” revealed “highly classified” information during those 2001 meetings, including details about CIA sources, operations and communications systems, the FBI alleged in the affidavit. There are video and audio recordings of the meetings, the affidavit said, suggesting U.S. intelligence was aware of them beforehand and had a source on the other side.

Ma stayed in contact with Chinese intelligence officers after he began working for the FBI in 2004, and copied classified documents in exchange for money, according to the affidavit. During an undercover operation that began in 2019, Ma allegedly told an FBI employee posing as a Chinese intelligence officer that he wanted to see “the motherland” succeed.

That case is not unique: China has lured other former U.S. intelligence employees with cash, getting U.S. government secrets from people no longer sworn to protect them.

“Preventing that is really, really tough,” said former Justice department prosecutor Ryan Fayhee. “They’re no longer subjected to periodic polygraphs, reinvestigation, all the stuff you have to go through to maintain a security clearance at the top level.”

China’s ability to target former officers is “certainly impressive,” said Jeff Asher, a former CIA officer himself, but “for the most part, the types of penetration that we saw at the height of the Cold War — Robert Hanssen and Aldrich Ames — we haven’t necessarily seen from Chinese intelligence.” Hanssen, an FBI agent, and Ames, a CIA counterintelligence officer, both spied for the Soviet Union and later for the Russian Federation, compromising human sources and other sensitive materials.

Former officials can offer “quite a lot” to adversaries, said Nicholas Eftimiades, a retired intelligence officer.

“A former intelligence officer has a lifetime of knowledge of intelligence techniques, operational techniques, assets that they had, information that’s been stolen,” Eftimiades said. “Then also the possibility of turning around and going back into the system or through friends in the system, getting more current operational intelligence.”

The case of Jerry Chun Shing Lee has been the “most devastating” among recent China episodes, according to James Olson, the former chief of CIA counterintelligence and author of “To Catch a Spy.”

The FBI monitored Lee — who worked for the CIA from 1994 to 2007, including in China — for years before his arrest in 2018. After leaving the agency, the former CIA case officer started a tobacco company in Hong Kong with an associate who had ties to Chinese intelligence. Lee began meeting with two officers from China’s Ministry of State Security, who asked him to reveal sensitive information and said they would take care of him “for life.” Lee reapplied at the CIA and had several interviews in 2012 where he lied about his meetings with Chinese intelligence officers and the source of his income. Lee was paid more than $840,000 for his work, prosecutors alleged.

Olson suspects Lee revealed the identities of the CIA’s sources in China, but prosecutors did not prove he gave classified information to China. Lee pleaded guilty to conspiracy to deliver national defense information to aid a foreign government, after FBI agents covertly searched his hotel room in 2012, finding notes with detailed information about CIA assets he handled as a case officer. He was sentenced to 19 years in prison in November 2019.

“In just over a year, we have convicted three Americans for committing espionage offenses on behalf of the Chinese government,” John Demers, the Department of Justice’s top national security official, said in a statement following Lee’s sentencing. “Sadly, all three of them are former members of the U.S. Intelligence Community. These convictions and sentences should send a strong message to current and former security clearance holders: be aware that the Chinese government targets you.”

Another former CIA case officer, Kevin Patrick Mallory, was handed a 20-year prison sentence in May 2019 for selling classified documents to a Chinese intelligence officer.

Four months later Ron Rockwell Hansen, a former Defense Intelligence Agency officer, was sentenced to 10 years for trying to pass defense secrets to China. Kun Shan Chun, a former FBI electronics technician, was given a 24-month sentence in 2017 for disclosing information about the bureau’s surveillance techniques and targets to at least one Chinese government official.

Perhaps most embarrassing for the FBI was the case of Katrina Leung, a businesswoman recruited by FBI agent James Smith in 1982 to report on her contacts in China. Smith and Leung had a 20-year affair and the FBI agent shared operational details with the businesswoman, who was also working for Chinese intelligence, the bureau alleged. The FBI arrested the pair in 2003, but a judge later dismissed charges against Leung, citing prosecutorial misconduct.

CIA spokeswoman Nicole de Haay declined to comment. FBI spokeswoman Sutton Roach pointed to FBI Director Christopher Wray’s previous remarks warning of a broad espionage threat.

It can take years to gather enough evidence for federal prosecutors to successfully prosecute a defendant who allegedly spies for China. U.S. intelligence agencies can spend years surveilling suspected spies to glean information about how rival intelligence services operate. The information in some cases can be so sensitive that officials determine it’s a risk to national security to reveal it in court.

But double agents aren’t just the stuff of movie scripts, and spies can tell on other spies when they’re under pressure or looking to increase their earnings.

“You have to assume many of these cases were broken because we had a source,” said Olson, the former head of CIA counterintelligence.

(Edited by Shenaz Kermalli, Kathryn Barnett and David Martosko.)

The post Espionage Cases Point to Chinese Infiltration of FBI and CIA appeared first on Zenger News.