MEXICO CITY — The Nueva Central Mexican restaurant had not recovered from the losses caused by reducing its capacity 70 percent while operating through the pandemic when it suffered another setback.

Located in the Villa Hermosa neighborhood in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, in northern Mexico, the restaurant had a power and water outage on Feb. 15. Two days later, it ran out of gas, which is essential to cook for the nearly 1,000 diners the establishment serves every day.

“We had to adapt,” said Juan Alemán, the restaurant’s general manager. “We bought coal and converted the stove from natural gas to propane to resume operations. But we had not budgeted for the expense.”

The winter storm in the United States, especially in Texas, affected the availability of natural gas. The pipelines froze, and prices increased in an “unusual and exorbitant” way, reported Mexico’s Federal Electricity Commission (CFE, per its initials in Spanish), a state company, as did the country’s National Center for Energy Control (Cenace), the public body operating the electricity system.

According to media reports, an energy unit went from $3 to $150, on average.

Power plants in northern Mexico operate on natural gas. The interruption of electric power due to a lack of this resource affected 26 states and 42 million users.

The outage affected about 2,600 companies in Mexico, and the losses amounted to $2.7 billion, according to information from the National Council of the Twin Factory and Export Manufacturing Industry.

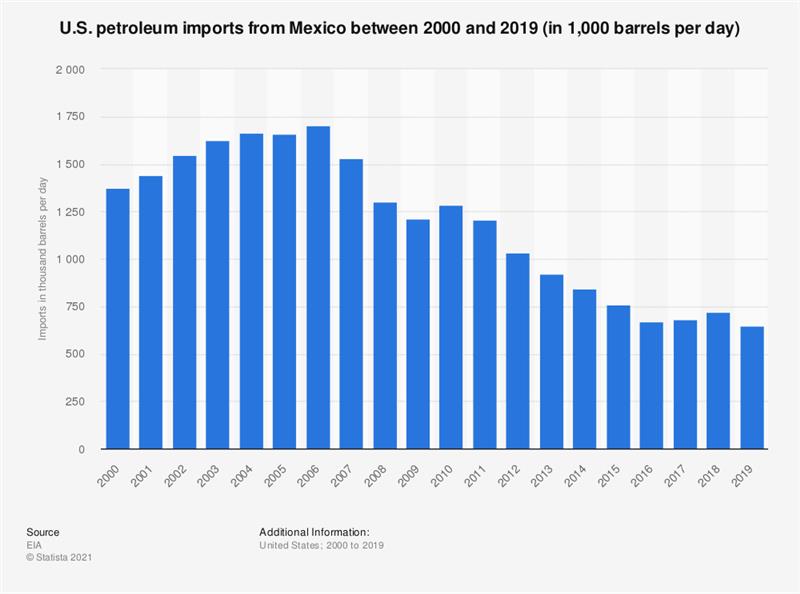

The outage made evident Mexico’s dependence on this hydrocarbon and on the United States, said Isidro Morales, a non-resident scholar from Rice University’s Baker Institute’s Center for Energy Studies.

Natural gas is the source of 64 percent of Mexico’s electricity, and 70 percent of it comes from the United States.

“Any unexpected change in the gas supply immediately impacts electricity generation, and that puts Mexico in a vulnerable position,” said Morales.

Dependence increased in recent years because Mexico can buy natural gas at low prices from the United States, which has become a significant producer. But the blackout showed that it won’t always be cheap.

When it comes to natural gas, Mexico’s energy future is uncertain, since it cannot become self-sufficient in the short term. The current administration does not have the resources to modernize the electrical infrastructure and has canceled private investments directed toward this purpose.

Cheaper to import than to produce

Since 2000, the Mexican government has opted for natural gas as a transition energy source toward renewable energies.

Mexico has gas reserves both underground, associated with oil exploitation, and in above-ground deposits. But its extraction is expensive, and that associated with oil drilling dropped as Pemex’s production fell. Pemex is the state-run oil company, and while an important energy partner with the U.S., it has many operational inefficiencies that make its operations costly.

“The strategy that previous administrations outlined regarding natural gas included developing gas pipelines to transport it and developing unconventional resources (shale gas) in the north of the country. It also meant repowering the extraction of gas processing complexes (associated with oil production) in the Gulf of Mexico,” said Ricardo Granados, a member of Ombudsman Energía México, an organization seeking to defend the right to energy access.

The government canceled the tenders planned for its exploitation in 2019, and the private oil licensing rounds that sought to reverse the decline in Pemex production. “You had the first part implemented, gas pipelines, but you are not producing the gas,” said Granados.

Meanwhile, natural gas imports have continued to rise. “There are no incentives for Pemex to produce more gas because it is cheaper to import it,” said Morales. “CFE already has an agreement with gas transportation companies promising to import it for 30 years.”

He argues energy reforms must continue for Pemex to operate more efficiently.

Getting to the root of the problem

Mexicans suffered a previous blackout on Dec. 28, 2020. Caused by two transmission pipelines between Nuevo León and Tamaulipas that went out of operation, the outage affected 10 million people in 12 states.

The blackouts warn of the need for investment to strengthen the electricity infrastructure, which the government-run company cannot do by itself. “There is a lack of investment in transmission pipelines and gas storage [that prevents Mexico from] achieving supply security,” said Gonzalo Monroy, a consultant specializing in the energy sector.

Investment in storage would help secure backup gas reserves for critical moments. The previous administration set projects for tenders but canceled them in 2019, Monroy said.

The 2013 energy reforms opened the sector to private investment, for which it implemented tenders and auctions. The electricity sector created the Wholesale Energy Market, in which power generating companies and the CFE participate. They sell energy to suppliers that work to meet national demand, among them the state company.

This possibility triggered the participation of renewable energy generating companies, mainly wind and photovoltaic. Their involvement was in tune with one of the priorities of the reform: generating 35 percent of electrical energy with renewable sources by 2024.

Electric energy from clean sources is a viable alternative to reduce dependence on natural gas, said Morales.

But in 2019, Cenace canceled the fourth clean energy auction. The previous administration carried out three, and the auctions did not resume.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has criticized private energy companies, especially clean energy firms. He said energy reforms enacted in the country give preferential treatment to private companies, with “leonine contracts,” and that the CFE was left out.

Obrador said energy reforms seek to weaken and eliminate government-run companies, such as Pemex and CFE, adding that Mexico’s energy vulnerability could decrease if the country recovers energy sovereignty, strengthening its companies.

“The companies belong to the people of Mexico. We need to strengthen them [if we want] to be independent and guarantee that electricity, gasoline, diesel and gas prices do not increase,” he said on Feb. 24, at a conference where he thanked the legislator for voting for his proposals to the Electricity Industry Law.

The consequences of going back to the past

If CFE becomes the leading energy supplier again, as it used to be before energy reforms, Mexico will remain vulnerable, experts said.

Five days after the February blackout, the government declared an environmental emergency in Salamanca, Guanajuato. Due to the lack of natural gas, a CFE thermoelectric plant used a higher fuel oil amount than the allowed.

CFE used all its generation capacity, which includes hydroelectric, geothermal, fuel oil, coal, nuclear, diesel, geothermal and combined cycle (fuel oil and coal) plants.

In normal conditions, CFE’s fuel oil plants are the last to come into operation, under the dispatch rules enforced since 2013. “The power plants with the lowest short-term cost are the first from which energy is purchased,” said Monroy.

The current government tries to make regulatory changes to strengthen state companies. It proposed reforming the law to dispatch CFE plants first, regardless of their high generation costs.

“The oldest and most inefficient plants — the fuel oil, coal and turbo gas plants — would operate at 100 percent [capacity],” said Monroy. Private companies would be left for last. But a judge ordered the suspension of the reform decree, saying that it would mean higher power costs, an increase in electricity rates and the violation of various international treaties.

Experts do not rule out more attempts to make the state-owned company prevail. “The best public policies are those that put the final user at the center, regardless of which government is in office,” said Edgar Alvarado, a member of Ombudsman Energía México.

(Translated and edited by Gabriela Olmos. Edited by Bryan Wilkes and Melanie Slone)

The post Blackout: Mexico’s Uncertain Energy Future appeared first on Zenger News.