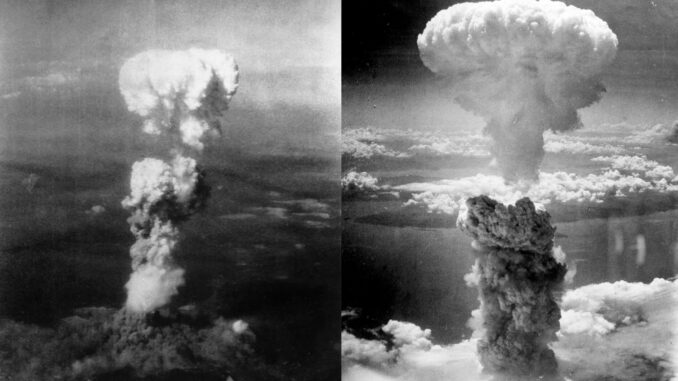

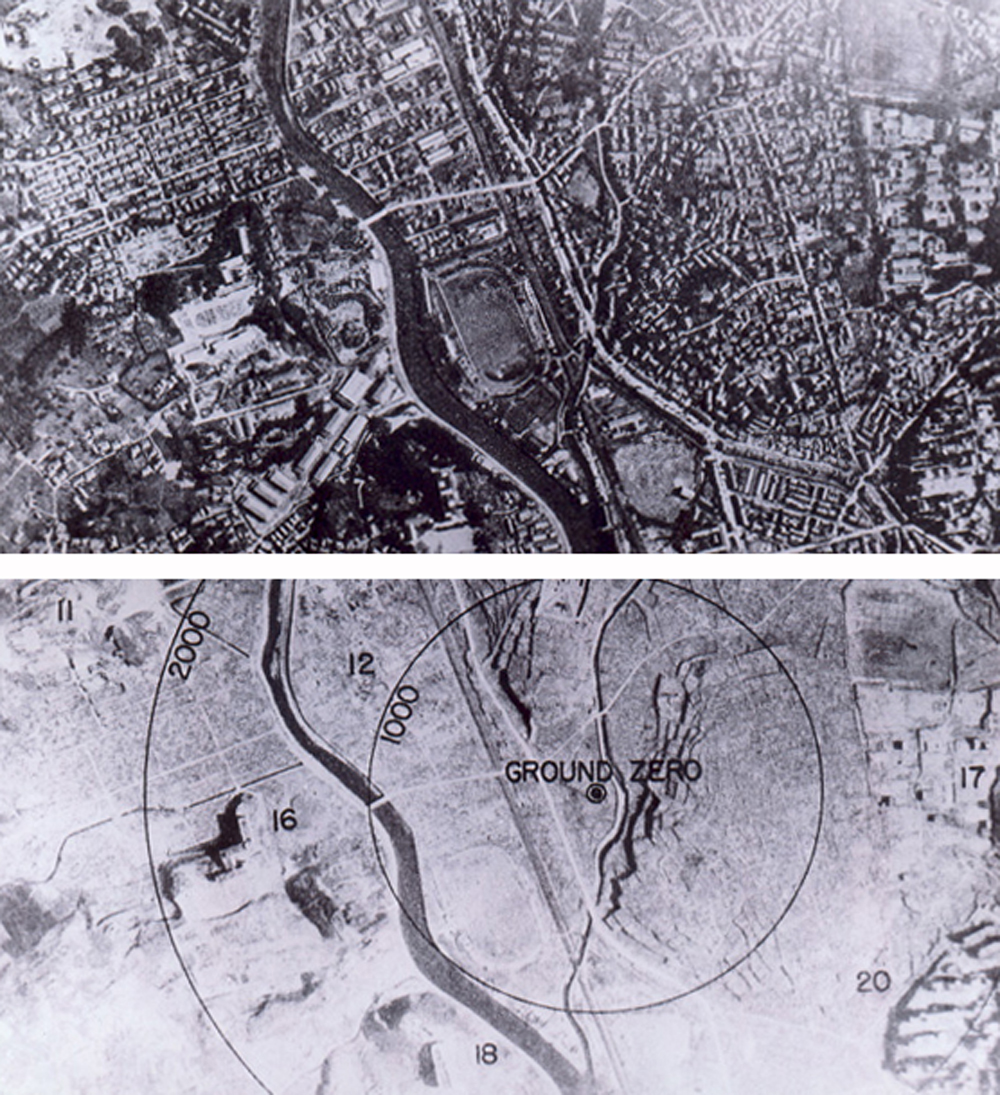

August represents the 75th anniversary of the U.S. military’s atomic bombings of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. Both cities were selected because they held important military and industrial value, though some today disagree. What is not disputed is both cities were decimated by the bombs in 1943.

The two incidents, usually linked together as one larger action, were the culmination of years of heated debate and scientific study—not just over its feasibility but over its morality.

“Seventy-five years ago, a single nuclear bomb incinerated the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Tens of thousands of men, women, and children were killed in an instant, and tens of thousands more died after terrible suffering in the days, weeks, and years to come,” wrote Matthew Bunn, Professor of the Practice of Energy, National Security, and Foreign Policy at Harvard University.

“Even today, beneath the city’s streets and in the city’s rivers, there remain traces of many innocent citizens who were reduced to mere ashes in a moment, their spirits filled with indignation,” writes Hidehiko Yuzaki, the former Governor of Hiroshima prefecture, in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists.

As a defining moment and generational trauma in Japanese history, it still provokes that very same debate nearly a century later.

“It was not necessary or justified to use nuclear weapons against japan. It was a reprehensible crime,” said one Twitter post with more than 100,000 likes.

it was not necessary or justified to use nuclear weapons against japan. it was a reprehensible crime

— Shaun (@shaun_vids) August 6, 2020

“Today is the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima by the United States. This unprecedented act of violence killed an estimated 100,000 people. Irrefutable historical evidence proves that the bombings were militarily unnecessary and morally reprehensible,” wrote another with nearly 3,000 likes.

Today is the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima by the United States. This unprecedented act of violence killed an estimated 100,000 people. Irrefutable historical evidence proves that the bombings were militarily unnecessary and morally reprehensible. pic.twitter.com/OZHeswiFTh

— gaming disorder pawg (@roun_sa_ville) August 6, 2020

Daryl Kimball, Executive Director of the Arms Control Association, is one such critic.

“There were several alternatives to the use of the bomb on Hiroshima and to the second use of the bomb on Nagasaki. There could have been a demonstration of the new weapon, as the group of Manhattan Project scientists proposed; there could have been the further prosecution of the war by the Americans and with the entry of the Soviets in early August 1945, it is quite clear that the Japanese high command would at that point have recognized their military situation to be impossible; and there could have been a pause after the August 6 attack to allow the Japanese leadership to absorb the significance of the bombing,” he said.

“The bomb that was used to destroy Nagasaki on August 9 hit a mere 10 hours after the official entry of the Soviets into the war on Japan and as the Japanese leadership were debating whether to surrender,” Kimball said.

It’s not an uncommon sentiment, either in Japan or anywhere else. The bombings are also unavoidably politicized. A common talking point among the Japanese right-wing for decades has been to have the United States apologize for the bombings.

When President Barack Obama visited the Hiroshima Memorial in May 2016, he drew criticism from some American conservatives for the perceived apology, and likewise criticism from locals for only expressing sympathies and not actually apologizing.

Before Obama’s visit, Chinese state-run news outlets blamed Japan for the bombings and said they were justified to bring an early end to World War II, avoiding protracted warfare and saving more lives.

That seems to reflect a general historical consensus among most Americans, that the bombings were a deadly but necessary alternative to the horrors of a prolonged land invasion of the Japanese mainland.

“Even after winning dozens of major battles against Japan, they showed no willingness to surrender. No one was certain that these bombs would force a Japanese surrender and in fact the Japanese signaled the opposite after the first bomb, and of course did not surrender,” said Jeff Crater, co-founder of the Advanced Nuclear Weapons Alliance Deterrence Center. “It was only after the second bomb did Japan surrender, likely figuring the United States could have additional nuclear weapons it could use to destroy military industrialized Japanese cities, co-located with tens thousands of Japanese citizens.”

“Japan knew they were defeated after Midway, but could not bring themselves to admit the consequences which were surrender or fight to the very end,” said Peter Huessy, Director of Strategic Deterrent Studies at the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies. “Japan gave it citizenry instruction on how to resist, how to use kamikaze weaponry against U.S. ships, how to dig caves and remain in resistance. The estimated casualties were 1 million U.S. and Allied and 3-5 million Japanese, based on real figures from real battles.”

That latter statistic remains contentious. “In July 1945, Truman was briefed on the the U.S. miitary’s assessment that a full-fledged invasion of Japan might result in 40,000 American military deaths and some 150,000 wounded,” said Kimball of the Arms Control Association. He said somehow that number expanded significantly, so that by 1947 when the bombing was already in the past, “it was cited by former Secretary of War Stimson in his February 1947 article published in Harper’s to defend the decision to drop the bombs.”

A decision which, according to Kimball, was not even a matter of military consensus. “There was no consultation with key members of the ‘war brass’ including General MacArthur and General Eisenhower, who expressed his view that the use of the bomb was not necessary to end the war, and Admiral Halsey, who later said it was a mistake in part because the Japanese had put out a lot of peace feelers and had been contemplating surrender as early as May 1945,” he said.

In Kimball’s eyes, the bombings were as much a political maneuver against the threat of Soviet power as they were a swift defeat of Japan.

“The historical evidence, including Truman’s diaries and his communications with senior advisors, makes it very clear that those who approved and pushed the use of the bomb on Japan believed it would have value in sending signals to other countries, particularly the Soviet Union, in the post-war world,” he said. “President Truman and his advisers were aware of the alternatives, but Truman chose to authorize the use of the atomic bombs in part to further the U.S. government’s postwar geostrategic aims vis-a-vis the Soviet Union.”

The Soviet Union, which helped conquer Berlin and invaded Japanese-controlled territory earlier in the year, could have driven the Japanese surrender according this interpretation.

“The entry of the Soviets in the war against the Japanese in Manchuria beginning August 8 was another very significant factor… We can only speculate about the costs and to whom, but the body of evidence we have today suggest that the use of the Hiroshima bomb, and certainly the Nagasaki bomb, were not necessary to achieve Japan’s surrender in the summer of 1945,” said Kimball.

“Undoubtedly, the Soviet Union’s entry into the war on August 9 was critical,” said Sharon Ann Squassoni of George Washington University. “This was no surprise — under the terms of the Yalta agreement, they were bound to join the Pacific theater of war by August 9. The Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov delivered the declaration of war to Japan’s ambassador to the Soviet Union Naotake Sato on August 8th and the invasion began shortly after midnight.”

A year after the bombings, the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey concluded that the bombings were unnecessary to ending the war, saying “it seems clear that, even without the atomic bombing attacks, air supremacy over Japan could have exerted sufficient pressure to bring about unconditional surrender and obviate the need for invasion.”

Surrender through this method would not have been unconditional nor ideal, said Huessy.

“A ceasefire or armistice would have left in place Japanese forces in China and Korea and throughout the Pacific and Southeast Asia,” he said. “Negotiations would have had to be undertaken in multiple countries with multiple actors with no standard outcome. The Soviets promised regular elections throughout Eastern Europe, and of course reneged on all those promises at Yalta, and we know the outcome: totalitarian rule until the end of the Cold War.”

(Editing by Bryan Wilkes and Allison Elyse Gualtieri.)

The post 75 years later, atomic bombings still provoke debate appeared first on Zenger News.